Before attempting to join the dots I will give a word of warning. This chart offers no evidence, only suggestions.

1086 – First Generation

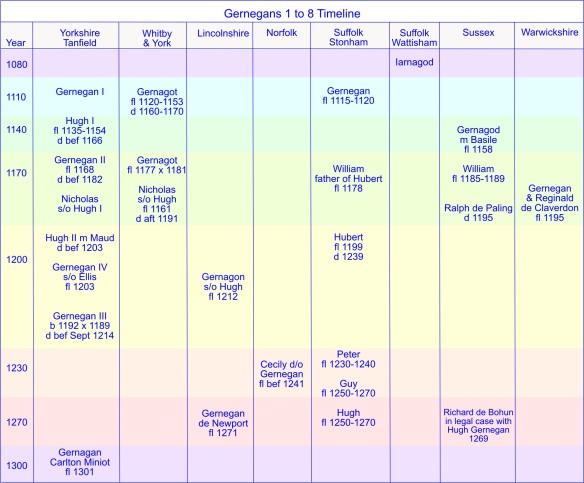

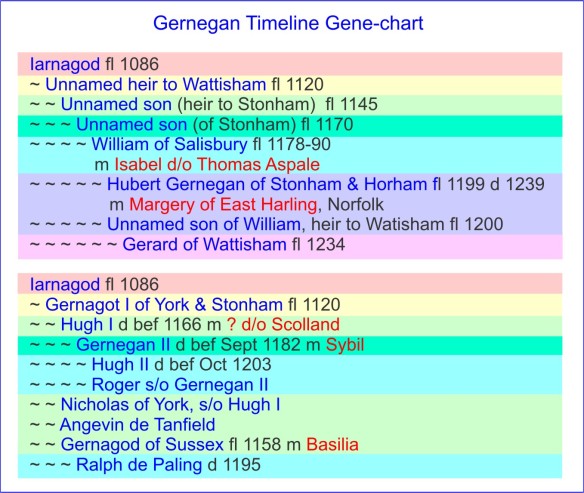

We have already seen that Gernegan II of Tanfield was the (second) canon Gernagot at York who retired to Whitby to be a monk.

Now we also see that the ‘speculated’ Gernegan I was almost certainly the same man as the first canon Gernagot at York. It would be a huge coincidence were he not. It would be a further coincidence were he not Gernegan 5 of Stonham who witnessed a charter at Eye, in Suffolk, in ca 1115.

There is a hidden story here that bleats to be out, and our first inkling of it is with the Domesday Holder Iarnagod with the land he held of Eudo FitzSpirewin at Battisford and Wattisham. It might help if we understand what happened in the years following the Norman Conquest.

Post-Conquest Settlement of England

Historians speak in sweeping terms: “Having won the Battle of Hastings, William then doled out the conquered land to his followers.” While this is true in as much it says, it leaves much unsaid.

William rewarded his most trusted magnates – who just happened to be his most dependable commanders – with land which had seen most of the recent action; ravaged, its English lords slain, this was the southern counties. More land was available, more scattered, through the forfeiture of Harold Godwinson, of his brothers and sons, and of his supporters. These lands, then, were the first to be reassigned.

There then was a lull. At this point, apart from the lands already assigned, all of England’s lands were in William’s hands be they the possession of the Church, of the few surviving English magnates, of the many freemen of the former Danelaw, of the Bretons who had already settled there. And if the Church, the English, and others, wanted their land back then they must pay for it with both silver marks and relic-sworn oaths.

William was not unreasonable; he allowed the English, Church included, sufficient time to raise the funds, and decided which side their bread was buttered. But many of these lands were held now by widows, their husbands killed in the two battles that year, plus the many local uprisings. William quickly married them off to ‘suitable’ Norman, Flemish or Breton lords. But many widows preferred marriage to a different ‘lord’. They fled to the convents taking the deeds to their lands to lay upon the altar as gifts (and William could not gainsay them).

The next few years saw a rash of rebellions erupting – in the North and West, the supporters of Edgar Æthling; in the East at Ely, Hereward and a remnant of the Mercian men. At each rebellion more English lands were forfeit – and more Norman supporters were rewarded.

In 1075, while William was ‘over the sea’, Waltheof, the English earl of Northumberland, Roger de Breteuil, son of William FitzOsbern, earl of Hereford and one of William the Conqueror’s most ardent supporters, joined with Ralf de Gäel, the Breton earl of Norfolk and Suffolk, in the ‘Revolt of the Earls‘.

Lanfranc, archbishop of Canterbury, acting regent, dealt with the uprising. He had no liking of Bretons. He claims to have eradicated them. Though he did remove a large numbers from Norfolk, yet he left many still holding lands in Suffolk. All this can be gleaned from reading the Domesday Book. It is not merely a record of landholdings, but the story of Post-Conquest England, with all of the outrage, and all of the petty squabbles, and a distinct lack of humour.

It would be wrong to imagine the Norman, Breton and Flemish magnates or lesser lords, packing their bags and leaving home to settle anew in this new land. Except for a few who might seek escape, it didn’t happen like that – England was not so far away. No doubt there were those who didn’t even deign to cast a cursory glance at their new property, their only concern: How many manors? How much their worth? What do they yield? In this first generation, it was the younger brothers, the cousins, the trusted servants, the favourite knights, who were subfeudated to their lord’s new lands. Amongst these would be one appointed as ‘overseas steward’ to his lord’s estates.

The other thing to note is that William didn’t give this land for free. He stated how many knights each allocation was to provide. While later, attempts were made to base this knight-service upon size of land, as yet there was no system to William’s demands. He could as easily have pulled the numbers from the top of his head. We might think the best way to cope with this demand was for the new lord to use his lands to subfeudate his knights, and there is sign of this happening in the Domesday Book. But it seems almost the exception. Besides, at this period most magnates had their own standing armies, and did many of the lesser lords. So while some subfeudated tenants were indeed knights, most in this first generation were not.

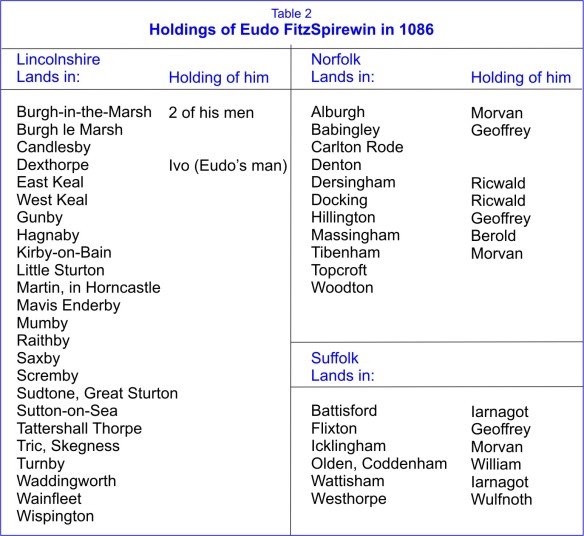

Iarnagod

It takes little imagination to realise that Iarnagod was a member of Eudo FitzSpirewin’s household; a younger brother, maybe; a nephew; a trusted servant – his chaplain perhaps, now growing old. Eudo FitzSpirewin was not a magnate – in fact, though he is of Breton origin, he cannot be traced in his homeland. Thus, his land-grant was likewise small. Concentrated in Lincolnshire, with the exception of Daxthorpe, only those manors in Norfolk and Suffolk were subfeudated. See Table 2, FitzSpirewin’s Holdings 1086.

1110-1150 – Second-Third Generations

It is not much to suppose that Iarnagod married and had sons who survived him. One can imagine the elder son (his heir), raised in the knowledge that one day Wattisham and Battisford would be his to hold of their liege-lord, Hugh Brito of Tattershall, would be sent to Tattershall castle, in Lincolnshire, to receive a knight’s education – while the younger son was sent to York, to equip him as a cleric. We have no name for the elder son, but we know of the younger. He was Gernagot.

At St Peter’s, York, Gernagot excelled in his studies. We know this for he remained with the archbishop to become part of his administrative team. But before he’d received such an accolade, he had caught the attention of King Henry I. King Henry, a busy man, was newly Lord of Eye. He could use Gernagot’s skills. He tried to pry him away from St Peter’s – King Henry was known for his patronage of young clerics. He granted him land of the honour of Eye – at Stonham. Stonham was less than 10 miles away from his brother’s estate. But who knows what the family tensions; that very proximity might have been the deciding factor, why he remained with the Church.

In York, Gernagot married, and had sons – or at least one that we know of: Hugh. Gernagot ensured him a good education that equipped him to serve as a steward. Perhaps the father hoped to place the son with the king, at Eye, or with Hugh Brito at Tattershall. Whatever the plan, we know that he served for some short time as steward to the honour of Richmond where, I suspect, he married the daughter or sister of Scolland.

It is possible that Gernagot I of York had a second son, named for himself: Gernagod. It is possible this son found favour, in 1138, with William d’Aubigny, 1st earl of Arundel, newly married to Adeliza de Louvain, widow of King Henry I. But there could be another story that accounts for his presence in Sussex.

1160-1200 – Fourth Generation

Hugh, sometime steward at Richmond, begot three sons that we know of (and possibly upon Scolland’s sister or daughter): Gernegan II of York and Tanfield; Nicholas canon at St Peter’s; and Angevin of Tanfield. Gernegan II married Sybil. On the Sussex coast, Gernagod married Basile. Is it coincidence that both Gernegan’s married a woman by the same name? Basile, Sybil, and many other variations, are pet forms for Isabelle.

But what story has this Gernegan II, son of Hugh, to take him to Sussex, to be a tenant of the Bohuns? If this Gernagod of Sussex is related, then I see him rather as the brother of Hugh, as above, not as the son.

There is another Gernegan member from this time-frame: William. Another canon – this was a feature of early-to-middle medieval Brittany: the Church was a career that remained in the family, be it the village priest who was of the same family, father to son for generations beyond count, or a bishop or abbot. There was no hint of celibacy here.

But William; was he a son of Hugh? He is not mentioned in the early charters of Richmond. But then, why would he be? He could have been already away to the south in Stonham, or Salisbury.

Or could William be a scion of Iarnagod’s elder son’s line? Does he belong amongst the ancestors of Gerard of Wattisham rather than belong to the Gernegan’s of Yorkshire?

To me this latter scenario seems the more likely. It would explain the otherwise missing 2 carucates from the Hubert’s estate. (See Gernegan 5 and 6.) Battisford and Wattisham together would add an addition 1 carucate and 40 acres; the rest would come from the other oddments of land that Hubert held e.g. Thornham Magna in Suffolk, and Hethel in Norfolk. And perhaps it was with William that the Yorkshire and Suffolk lines finally parted to become two separate families.

The story leaves some questions still hanging. What happened to Gernagot of York’s interest in Stonham? How did it revert to William, father of Hubert? One possible answer is that Gernagot left it to his nephew, his elder brother’s son. One would expect that of a Churchman.

There is also the question of Gernegan de Claverdon. Could he and his brother Reginald also be sons of Gernagod of Sussex? Or would that provide too neat a solution?

~ ~ ~

The additional research has turned up additional dots. In this post I have attempted to join those dots and make them a story. But that is all it is: a story, fiction. Unless it’s been stated as fact, all else is supposition. It remains for the reader, the student, the genealogist to decide how sturdy are the joints I have here wrought – or perhaps to find stories of their own.

~ ~ ~

The next post, provisionally scheduled for 12th February, will present ‘A Brief History of Brittany’ before we look for a likely source for Iarnagot, Domesday tenant of Eudo FitzSpirewin in Suffolk.

Crimson,

As always, wonderful work! I am going to have to go back through all of these again in more detail, but the layout, and research (as well as the creative narrative) give a very plausable picture. The information regarding the socio-eco climate, as well as tidbits about history and cultrue at the time really help rationalize the storyline. While there is circumstantial evidence in certain cases, and suppositions in others, this really helps form a more believeable story for the Jarnagin Family history than the one offered in ‘hisotrical’ documents.

As I noted in the past, I believe this line is my family line, and while I found the original story of a Danish/Viking origin fascinating, I could never find any support for it. I started leaning towards a Berton origin, and while I know that is not the final conclusion in your story, there is certainly a lot of support to suggest that Iarnogot was from Brittany.

Excellent! I look forward to your future postings…and thank you for your work!

I have never denied the possibility of the Breton origin; my query has been with 1: the form of name which while amply evident in Brittany, is not Breton – to be discussed in a later post; 2: your insistence upon the Bastard line. I believe I might have found a more acceptable source – again, to be discussed in a later post.

Meanwhile, I appreciate your comments, Sean, and would like to thank you here for your help and guidance in providing some of the links I’d not yet found. Thank you from CP.

I have two questions.

My first is what of the infamous “Prince Bryan”? He supposedly was at Somerleyton before 1066, and is listed in the Domesday Booke. Jernigans had held Somerleyton from prior to 1066 up til the 18th century despite changes in religion and how they fared with the royals (Whose Sandringham Castle is VERY near to Somerleyton in Kings Lynn).

My understanding was that the Jerninghams were the part of the line that “split off” to become Catholic and went to Costessey, which is just on the west side of Norfolk.

My second question, more of an interesting point, is that in the Scandinavian countries during the 900’s, Christianity was being brought in on the edge of the sword. Convert or die. Certainly many Danes chose the 3rd option of leaving, and there is some archaeological evidence of this currently being found. This could be what drove many Northern Europeans to cross the Channel and try their fortunes in a new land. While Christianity was present in the new country, they were not so vicious in their approach to conversion!

Whence the Prince Bryan? ask I. I have searched for the origin of this tale, and cannot find.

Francis Blomefield in his account of the Jerningham family in his History of Norfolk (parish: Cossey) reports of a Danish origin: “Anno M. xxx. Canute King of Denmarke, and of England after his return from Rome, brought diverse captains and souldiers from Denmark, whereof the greatest part were christened here in England, and began to settle themselves here, of whom, Jernegan, or Jernengham, and Jenhingho, now Jennings, were of the most esteem with Canute, who gave unto the said Jerningham, certain Royalties, and at a Parliament held at Oxford, the said King Canute did give unto the said Jerningham, certaine mannors in Norfolke, and to Jennings, certain manors lying upon the sea side, near Horwich in Suffolke, in regard of their former services done to his father Swenus, King of Denmark.” Here Jerningham was given land in Norfolk. Although Somerleyton lies close to the border, it was not included in Norfolk until a modern revision of county boundaries in the 1970s.

Blomefield makes no mention of ‘Bryan’, nor of princes. Furthermore, he debunks the very quote he has given. “That the above note may be in the pedigree of the family, I cannot contradict, nor yet the truth of it, though I must own, there are many things which seem to invalidate it.”

And whence the idea that “Prince Bryan” supposedly was at Somerleyton before 1066, and is listed in the Domesday Book? Supposedly ought to be written large. There is a possible ancestor of the Jernegan family mentioned in the Domesday Book, but that is Iarnegan. Somerleyton came late to the Jernegan family, inherited through an advantageous marriage in C14th.

(I suggest you read the entire Jerningham series on this blog – I intend, over the coming few days, to provide a drop-down menu of links to each post. Some may not interest you since my starting point was the Costessey Jerninghams. But from there I track back to the question of the rogue Prince Bryan.)

When I first began my inquiry, my approach was as is yours in Point 2. Why shouldn’t Gernegan be Dane? But it’s also true that the Gernegan name – in all its spellings – is amply evidenced in Brittany. And before you say it, yes I know that the Vikings also settled that area. However, as will be seen in the posts due next month, the Gernegan name pre-dates the Vikings. I am reluctant to say more here.

Oh, and I’ve just come across this (the source of the trouble):

= Weaver’s Discourse on Ancient Funeral Monuments, Page 502, ‘The Diocese of Norwich’ – ‘Somerly’: “The habitation in antient times of FITZ-OSBERT, from whom it is come lineally to the worshipful antient family of the JERNEGANS, knights of high esteem in these parts, saith CAMDEN in this tract … the name [of Jernegan family] hath been of exemplary note before the conquest ; if you will believe thus much as followeth, taken out of the pedigree of the JERNINGHAMS, by a judicious gentleman. [there follows the story of Canute given above]

Camden’s Britannia, which Weaver quotes – has: “Within the land, hard by Yare is situate Somerley towne, the habitation in ancient time of Fitz-Osbert, from whom it is come lineally to the worshipfull ancient family of the Jernegans, Knights of high esteeme in these parts.”

I hope this answers some of your questions, but as I said, I do recommend you read all the posts, bearing in mind that this second series (‘Gernegan Case Reopened’ thro’ ‘Gernegan Timeline’) has been in answer to new evidence, and thus my opinions and conclusions have changed.

And then of course, this document:

http://interactive.ancestry.com/8549/EarlyYorkshireFamilies-0029/199?backurl=http%3a%2f%2fsearch.ancestry.com%2fcgi-bin%2fsse.dll%3fgst%3d-6&ssrc=pt_t9723495_p24060751907_kpgz0q3d32799_m1&backlabel=ReturnSearchResults&rc=458,1279,686,1317;677,1336,829,1382;101,1370,250,1414;230,1497,379,1541;2400,191,2552,235

(“Early Yorkshire Families” LDS book)

States: that Hugh Jernegan of Tanfield (1120) had a grandson also Hugh who married Maud, daughter or Torfin, son of Robert. They held Manfield, and the Hughs held a moiety, until Hugh’s son died at Michaelmas of 1214. His daughter AND HEIR, Avice, married Roger Marmion, in whose family it (Manfield) descended.

To me, this seems to say that the line of the Hughs ended with Avice. Whether Avice (Alice?) was the daughter of the son of Hugh who died in 1214, or of Hugh himself, I’m still checking.

Again, I recommend you read the full series. Your questions are answered. I give links direct to source wherever possible. And those sources are primary, again where possible – where secondary I give preference to authors who have cited their sources. Where possible I root out those sources and read it for myself. Although I have had occasion to use genealogy-based sites, this has mainly be to gain access to Burke’s Peerage and others. Again, there is always the emphasis on materials cited.

You spoke of redistricting. Was the Norfolk area considered part of York prior to that? I’d been kind of ignoring the York connection as it’s so far from Norfolk.

I have recently read some very interesting things in books and studies about grave finds in East Anglia that may relate to the Jernigans. (Dress in Anglo-Saxon England by Gale Owen-Crocker is one) It seems that many grave finds, especially in graves thought to be of women, had three pins, one at each shoulder and one at the front of the garment. There are several sculptures showing this style, including the “Marcus Aurelius column” in Rome which attributes it to “the Angles”. It may be indicative of an earlier Germanic style as well.

Considering these finds, I realized the Jernigan coat of arms is – three buckles! Could this coat of arms be from recognition of “historic” dress styles of East Anglia? I noticed there are some other coats of arms in that area that also have three buckles.

It is an interesting tangle, these Jernigans. I am enjoying the search, that’s for sure!

Thanks for your research, I’m intrigued by the charts, and I will definitely read the source material!

Brandy (Jernigan) Grote

To clarify on your first point: the 1970s, Britain saw a major redrawing of the county borders – for political reasons. As a result many parishes sitting close to borders ‘moved’ into the neighbouring county. Somerleyton was one such affected; it had been in Suffolk, but now is in Norfolk.

Your suggestion of the Early Medieval Anglian source for the Gernegan coat of arms – the 3 buckles – while interesting, alas, has nothing to support it. Heraldic devices did not become common until post-Norman Conquest, although the use of a ‘badge’ (worn on a band on the arm by the lord’s knights and servants) was prevalent before then. But seldom does the badge motif match that of the later heraldic device,

But keep reading; who knows where the answers might be found.

Hi,

I don’t know your name. However, this history of the Gernegan-Jernegan lines and other contemporary lines is truly phenomenal. If you or any other males are thought to be related to these lines…I recommend taking a YDNA-37 test at FTDNA.com –which I think costs US$59.

PS: how do you make those customised little part-maps of the UK ??

Rgds

Gerard COLDHAM

gjcoldham@yahoo.com

Pingback: The Montfort Charter | crimsons history