We left the Jerningham story with Sir Peter Jernegan and his son Sir John now barons, tenants-in-chief, having inherited the manors of Somerley Town and Wathe, in North Cove, Suffolk. To continue . . .

Part 5 of the Jerningham Story

Manor of Wathe or Wade Hall or Woodhall . . .

“This manor was probably called after Robert Watheby, of Cumberland, who held it in the time of Hen. II [1154-1189]. From Robert de Watheby the manor passed to his son and heir Thorpine, whose daughter and coheir Maud married Sir Hugh or Hubert Fitz-Jernegan, of Horham Jernegan, Knt., and carried this manor into that family. He died in 1203, and the manor vested in his son and heir, Sir Hubert Jernegan.”

From W A Copinger, Manors of Suffolk, Vol VII

To clarify that:

Robert Watheby of Cumberland fl 1154-1189

~ Thorpine de Watheby

~ ~ Maud de Watheby m Sir Hugh/Hubert Fitz Jernegan d 1203

~ ~ ~ Sir Hubert Jernegan of Horham d 1239 m Margery de Herling

~ ~ ~ ~Sir Hugh Jernegan d 1272 m Ellen Inglesthorpe

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ Sir Walter Jernegan m Isabel FitzOsbert d 1311

Additional material from The Baronetage of England, Vol 1

Rev William Betham, 1801

How odd, then, to find this 60 years later:

“To Walter de Glouc[estria], escheator* this side Trent . . .

“. . . Order to deliver to Katharine, late the wife of Roger son of Peter son of Osbert, the manors of Somerleton, Wathe and Uggechale, co. Suffolk, Haddescou and Wyghtlyngham, co. Norfolk, which he has taken into the king’s hands by reason of Roger’s death, and to deliver to her the issues received thence . . .”

From the Close Rolls, Edward I, June 1306, volume 5

The manor was included in the inheritance of Katharine, late the wife of Roger son of Peter FitzOsbert, sister-in-law of Sir Walter Jernegan.

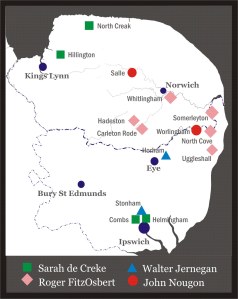

Then some thirty years later, when in 1338 Katherine died, we find the same inheritance – i.e. of Somerleyton, Wathe, Uggeshall, Hadeston (not Haddescou as given) and Whitlingham – divided between Sir Peter Jernegan and Sir John Nougon as Katherine’s late husband’s sole surviving heirs. Further, in 1362, when the last of the Nougons died, whatever they had held of the FitzOsbert inheritance landed fairly into the Jernegans’ hands.

To clarify that line of inheritance:

Osbert m Petronel or Parnel fl ca 1140

~ Roger Fitz Osbert fl 1216 d 1239 m Maud/Agnes fl 1249

~ ~ Osbert (possibly a late fictitious insertion)

~ ~ ~ Peter FitzOsbert of Somerley town d 1275 m Beatrix d 1278

~ ~ ~ ~ Roger FitzOsbert d 1305 m 1stly Sarah, dau/Bartholomew de Creke

~ ~ ~ ~ Roger FitzOsbert d 1305 m 2ndly Katherine d 1338

~ ~ ~ ~ Isabel Fitz Osbert d 1311 m (2ndly) Sir Walter Jernegan dbf 1306

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ Sir Peter Jernegan dc 1346 m (1stly) Matilda de Herling

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ Sir John Jernegan fl 1362 m Agatha Shelton

~ ~ ~ ~ Alice/Catharine Fitz Osbert fl 1281 m Sir John Noion of Salle d 1325

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ Sir John de Nougon d 1341 m Beatrice

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ Sir John de Nougon d 1349

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ John de Nougon d 1362 aged 17

So by what circuitous route did this manor of Wathe move from the hold of Sir Hubert Jernegan to that of the FitzOsbert’s – only to return some 60 years later?

The author of the Manors of Suffolk repeats the account of Davy (1769–1851). David Davy was the Suffolk equivalent of Francis Blomefield in that he traversed the county, nosing into churches and the great halls and shuffling around in their papers. He was what the Victorians called “an English antiquarian”, and he worked in conjunction with one Henry Jermyn. Their mss are currently held by the British Museum.

According to Davy, on the death of Sir Hugh Jernegan in 1272 the manor went to Roger son of Peter FitzOsbert. Which in effect shortens the manor’s stay in FitzOsbert’s hands to a mere 30 years.

Copinger remarks that Davy

“. . . apparently assumed the manor to have come to the Jernegans like the Somerleyton estate through the marriage of Sir Walter Jernegan with Isabella, sister and coheir of Sir Roger Fitz Osbert . .”

The way it is worded suggests that Copinger did not believe it. Yet the evidence is there in the Close Rolls. Wathe, together with Somerleyton, was inherited by Katherine from her deceased husband Roger FitzOsbert.

But how could the manor have passed from Sir Hugh Jernegan to Roger son of Peter FitzOsbert? Copinger doesn’t say ‘sold’, he says ‘went to’ and that implies Roger received it as inheritance.

Yet everywhere Sir Hugh’s heir is given as Sir Walter Jernegan – he who married the sister of Roger.

The only other means by which a manor might be passed as inheritance is if it were used as dower or dowery. Since we’re nowhere told of Katherine’s father, perhaps she was daughter to Sir Hugh Jernegan. Sir Hugh then bestowed the manor Wathe upon her as dowery, attracting a hefty-sized dower from Sir Roger her husband in return.

But as the order preserved in the Close Roll of Edward I, June 1306, later states:

“. . . the manors of Somerleton and Wathe are held of the king in chief . . . and the king has taken Katharine’s fealty for [them] . . .”

Were it not for that we could say that Katherine was Sit Hugh’s daughter. But a manor held in-chief of the king was not lightly used as dower or dowery. (see The Gentry Game)

So we ask again, how came it to be part of Katherine’s inheritance from her husband Roger?

To continue to Copinger’s account of Wathe Manor:

“. . . The King . . . granted the lordship of all [Sir Hubert Jernegan’s (d 1239)] large possessions, and the marriage of his wife and children to Robert de Veteri Pont or Vipont [Vieuxpont], so that he married them without disparagement to their fortunes . . .”

As witness the subplots of many a Robin Hood movie, the wardship of orphans and widows made for lucrative pickings. While delaying their marriage, the guardian – or warder as he usually was called – raked in the rents of his wards’ various holdings. The larger the holdings, the juicier the take. Why hurry the marriage in such situation. Some kings allowed this to happen, taking a cut from the profits. King Stephen (1135-1154) was one, King John (1199-1216) another. But other kings, particularly Henry I (1100-1135) and Henry II (1154-1189), empowered their sheriffs to act as the warders, thereby reducing the risk of abuse.

Sherefore Copinger’s statement, that the king granted the lordship of Sir Hubert Fitz-Jernegan’s large possessions, and the marriage of his wife and children to Robert de Vieuxpont, need be read as no more than that: Robert de Vieuxpont, as sheriff, was merely performing his usual duty.

But here we hit a problem. While it is true that Robert de Vieuxpont was a sheriff, in fact High Sheriff of Nottinghamshire, Derbyshire and the Royal Forests and later also High Sheriff of Westmorland, he died several years too early – in 1228.

Sir Hubert Jernegan died in 1239. Robert de Vieuxpont died in 1228.

Yet the position of High Sheriff of Westmorland was in the process of becoming hereditary. And so we find Robert followed, at least in 1235, by John de Vieuxpont, who in turn was followed in 1242, though for only a year, by a younger Robert, of a new generation. Thereafter, John de Vieuxpont 1242–1264, and the sisters Isobella and Idomea Vieuxpont 1264-1308.

But that’s not much help. In 1239-40 there was no Sheriff Robert de Vieuxpont. Anywhere. But it does move our focus northward.

Robert de Watheby of Cumberland

The first mention of Wathe manor finds it in the hold of Robert de Watheby of Cumberland. Copinger, following Davy and Jermyn, suggests it takes it name from de Watheby.

I would disagree, and point to several other manors and villages named Wathe, or Wade, which take their name from being next to a river – as is Wathe manor in North Cove. The name means a ‘wading place’. The same name underlies the Norfolk market town of Watton.

However, those who had access to more evidence than we, were convinced of the association. And so we must follow it.

Robert de Watheby held this manor of Wathe. But did he hold it as tenant-in-chief of the king? Or of some other northern-based lord?

If he held of another and said other was forfeit his lands, then the manor would have been granted to another. Robert de Watheby, or his heirs, would still hold it, merely the overlord has changed. In time it would have passed to Sir Hubert Jernegan and his son Sir Hugh, who would have held of this new tenant-in-chief.

It’s quite a story we are constructing. For it depends upon the manor coming to Sir Roger FitzOsbert as tenant-in-chief. At this point the Jernegans would have been his tenants and done fealty to him, as it is known they did for the manors of Stoven and Bugg.(See Betham’s Baronetage of England, Vol 1)

In this story, when Sir Roger FitzOsbert died, Katherine his widow would have become the Jernegan’s new overlord. And when she died . . . they became their own lords.

But was this what happened? It might help to determine it’s truth if we can find an overlord for Robert de Watheby. And for that we need first to find Robert.

In addition to the amazing collection of historical documents available at British History Online, there are also the County Histories. These mostly were written in 19th century, at the height of the Victorian craze for antiquities. In my trawl through these, hoping to find clues to the roots of the Jernegan tree, I came upon this.

To convert that to the form we’ve been using:

Archil

~ Copsi de Watheby fl 1146 m Goderida, dau/Hermer, lord of Kelfield & Manfield

~ ~ Robert de Watheby

~ ~ ~ Robert de Warcop

~ ~ ~ Alan de Warcop

~ ~ ~ Torphin de Watheby, lord of Manfield, fl 1210

~ ~ ~ ~ Robert d w/o issue

~ ~ ~ ~ Agnes m x 3

~ ~ ~ Matilda [Maud] m 1stly Hugh or Hubert, son/Gernegan d 1204

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ Gernegan m Rosamund dbef 1215

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ Avice dc 1284 m Robert Marmion d 1240

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ Nicholas

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ Hugh, son/Hugh fitz Gernegan

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ Isabel

I have particularly laid the chart this way, with Gernegan first and his brother Hugh, better given as Sir Hubert of Horham, third, despite that the above graphic shows the reverse, because Gernegan is given as Maud’s heir; Hugh is not though in this graphice he appears to be first-born.

Also, I have changed the year of Torphin’s demise. In the graphic it’s given as 1194 yet in the account of Torphin’s manor of Manfield we find this:

“. . . [Torphin de Watheby] who from 1169 to 1172 was one of the surveyors of the works of Bowes Castle, paid 2 marks for his lands in Richmondshire in 1210-12 . . .”

My italics

Which proves he was still alive in 1212.

Manfield is a parish in the North Riding of Yorkshire. Yet the above graphic was found in Records relating to the Barony of Kendale: volume 2 (1924), pp. 326-340.

Kendal and Westmorland.

As Wikipedia’s article tells us, in the medieval period, Westmorland was part of the greater Northumbria, i.e. that land which lies north of the Humber river yet not into Scotland. The eastern parts of Northumbria became Yorkshire, County Durham and Northumberland, while those to the west became Lancashire, Westmorland and Cumberland. Since 1974 Westmorland and Cumberland have functioned together as Cumbria.

For convenience, I’ll refer to the region north of the river Ribble as Cumberland and south of the river, yet north of the Mersey, as Lancashire.

In pre-Roman times this entire north of Britain, south of Carlisle, was home to the Brigantes, “the hill tribes”. It might be argued that even in 6th century, while the Angles were establishing their kingdoms of Deira and Bernicia, the Brigantes still held there, despite the 400 years of Romanisation. But Brigantes or not, the tribes here were Britons, akin to the Cornwallians, Bretons and Welsh. And to their north lay the equally British kingdom of Strathclyde.

Yet already by then, those piratical Celts from northern Ireland, known to the Romans as Scotti, had established themselves along the west coast of Scotland, centred on Argyll, and with claymore in hand had proceeded to dominate Scotland’s native population of Picts. Hence the northern reaches of Britain are known as Scotland, not Pictland.

There was another ethnic group here, come as raiders, soon to settle and take wives from the Britons, Scots and Picts around them. The Norsemen. They are often forgotten, so well did they blend with their hosts. In Russia, within two generations the Viking founders of Novgorod and Kiev had all but disappeared into the local Slavic population.

After the Vikings came the Normans. William I made small inroads. His son, William II, aka Rufus, is said to have conquered the region. Thereafter it was the Anglo-Normans who (most often) held this north western corner of Britain.

The Anglo-Norman hold was tenuous. The Britons, Picts and Scots frequently raided south into Northumbria and Cumberland. Or at least in the histories written by the English it’s the Scots etc who raided south. I’m sure the Scots would say it was the English raiding north. Either way, this entire area resembled a beach with an ever-advancing/retreating strand-line. Who owned the beach and who the sea depended upon one’s affinity. It was a situation that didn’t stabilise until after 1603 when England and Scotland shared a king.

It is therefore easy to see how in Cumberland the wise holder of land was he who knew how to swiftly change sides, swearing fealty first to one overlord, then to another, to English, to Scots.

The tenants-in-chief of Lancashire and Cumberland

- Pre-Hastings

Lancashire was held by Harold’s brother Earl Tosti, Thorfinnr and a few English thegns. - 1086 (Domesday Survey)

Lancashire was divided between the king and Roger de Poitou

An occasional manor was held by an old English thegn, e.g. Arnulf, Orm, Dwan, Ulf, Thorulf.

Earl Hugh of Chester also had a foot in.

Throughout this region the king’s lands were under the charge of the sheriff of Yorkshire. The holdings of Roger de Poitou, also tenant-in-chief of extensive holdings in the Midlands, Lincolnshire and East Anglia, were held of him by a notorious pluralist, Ernwin the priest; Ernwin held of Roger de Poitou in other counties too.

- Pre-Hastings

Cumberland – or at least the more westerly parts abutting Yorkshire – was divided between Earl Tosti and Thorfinnr (Torfinnr shares his name with the later Torphin de Watheby)

The southerly area, abutting Lancashire and known as Kentdale (later Kendal) was in the hands of one Gillemicel. (Micel here is not intended as the archangel Michael, but is Micel as in Mickle or Muckle Hill, i.e. big.) - 1086 (Domesday Survey)

Cumberland – or that part into which King William had made a wee inroad – was, as you’d guess, in the hands of the king and Roger de Poitou. Almost exclusively.

This changed when, as said, in 1092 William II invaded and conquered the area.

Wikipedia’s article on the County of Westmorland says that William II then divided Cumberland into the baronies of Kendal and Westmorland, although the article on the barony of Westmorland says the area was divided and made into baronies only in the reign of Henry I (1100-1135). But what’s the difference of 10 years between tenants and overlords.

Baronies of Kendal and Westmorland

To quote Wikipedia’s article:

“The Barony of Kendal is a subdivision of the English traditional county of Westmorland. It is one of two ancient baronies which make up the county, the other being the Barony of Westmorland (also known as North Westmorland, or the Barony of Appleby).”

In other words, the barony of Appleby, or Westmorland, lies to the north. And the barony of Kendal ( anciently Kentdale) occupies the south – abutting Lancashire.

To return to 11th century: William II, alias Rufus, granted his portion of Cumberland, including parts surrendered by Roger of Poitou, to his royal steward, Ivo de Taillebois.

Ivo had accompanied William I from Normandy, and had played a prominent part in breaking Hereward the Wake’s rebellion in 1071. An astute player of the Gentry Game, he had married Lucy, daughter of Turold, sheriff of Lincolnshire in whose name he later held the Lincolnshire ‘honour of Bolingbroke’. It is rumoured, but no where documented, that said daughter Lucy was granddaughter of the English Mercian earl, Alfgar. It is also only a rumour that Lucy was daughter of Turold for she is documented as being his niece. (See below, The Foundation of Medieval Genealogy)

Ivo de Taillebois is a good place to start our quest for the region’s tenants-in-chief circa 1238-72, the reign of Henry III (1216-1272).

From Wikipedia’s article on Ivo de Taillebois we can construct this gene-chart:

Ivo de Taillebois m 1stly unknown

~ Beatrix m Ribald, brother of Alan, Lord of Richmond

Ivo de Taillebois m 2ndly Lucy, dau/Turold of Lincolnshire

~ unnamed daughter m Eldred of Lancaster

The Ancient Families site, fair-brimming with genealogies from Bagabigna of the Armenian Orontid dynasty (fl 550 BCE) to George V, King of England, 1910-36, passing through every European country along the way, would make a more useful resource if each entry carried at least a note of its source. However, Ancient Families does provide us with the following, starting at the family’s origins in Normandy:

Reinfrid Taillebois

~ Ivo de Taillebois of Lincoln & Kendal m 1stly Gundred, dau/William Earl of Warenne

~ ~ Gilbert de Taillebois

~ ~ Orme de Taillebois

~ ~ William de Taillebois

~ ~ dau m Richard de Morville

~ Ivo de Taillebois of Lincoln & Kendal m 2ndly Lucy, dau/Turold of Lincolnshire

~ ~ Beatrix Taillebois m Ribald, illegitimate son /Eudes, Count of Penthievre

~ ~ ~ Ralph Taillebois m Agatha, dau/Robert de Bruis

~ ~ ~ ~ Robert Taillebois m Helewise, dau/Ranulph de Glanville

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ Randolph Taillebois m Mary, dau/Roger Bigod, Earl of Norfolk

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ Ralph Taillebois m Anastasia, dau/William Percy

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ Mary d 1320 m in 1270 Robert Neville

~ Gilbert FitzReinfrid

~ ~ William of Lancaster

Anyone with passing knowledge of the nobility of the day will recognise at once the heavy-weights in this gene-charts.

In contrast to Ancient Families lack of references, the Foundation of Medieval Genealogy’s website not only provides the sources but each is given in full and discussed. The site represents a major resource for any historian researching the period. Though the authors make no attempt at presenting in graphic form (wisely), from the quoted charters I picked out the following:

Ivo de Taillebois d 1094 m 1stly daughter/William Bardolf

~ Beatrix m Ribald, illegitimate son/Eudes, Count of Penthièvre

Ivo de Taillebois d 1094 m 2ndly Lucy d 1138, niece/Thorold of Lincolnshire

~ daughter m Eldred

~ ~ Ketel fl 1120 m Christiana, dau/unknown

~ ~ ~ William

~ ~ ~ Orme m 1stly Gunhilda, dau/Gospatrick, Earl of Northumberland

~ ~ ~ Orme m 2ndly Ebrea, dau/unknown

~ ~ Goditha m Gilbert de Lancaster, son/unknown

~ ~ ~ Roger m Sigrid, widow/Waltheof

~ ~ ~ Robert

~ ~ ~ Gilbert de Lancaster

~ ~ ~ Warin de Lancaster dbef 1194 m unknown

~ ~ ~ ~ Henry de Lancaster fl 1190

~ ~ ~ William “Taillebois” de Lancaster, Baron of Kendal, fl 1166 m 1stly unknown

~ ~ ~ ~ Hawise de Lancaster m 1stly William Peverel of Nottingham

~ ~ ~ ~ Hawise de Lancaster m 2ndly Richard de Morville^

~ ~ ~ William “Taillebois” de Lancaster m 2ndly Gundred de Warenne^^

^ Richard de Morville was son of Hugh de Morville & Beatrice de Beauchamp.

^^ Gundred de Warenne, widow of Roger de Beaumont Earl of Warwick, was daughter of William de Warenne Earl of Surrey and his wife Elisabeth de Vermandois

To continue:

~ ~ ~ William “Taillebois” de Lancaster m 2ndly Gundred de Warenne

~ ~ ~ ~ Jordan dbef 1160 (may have been child of 1st marriage)

~ ~ ~ ~ William de Lancaster fl 1156 d 1184 m Helewise, dau/Robert de Stuteville

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ Hawise de Lancaster m 11884-89 Gilbert FitzRoger FitzReinfrid Lord of Kendal

Gilbert FitzReinfrid

Against this documented chart, the chart provided by Ancient Families holds reasonably well – until one reaches Gilbert FitzReinfrid, there given as brother of Ivo de Taillebois and father of William de Lancaster. Yet by the evidence of the charters he was definitely the husband of Hawise de Lancaster, daughter of William de Lancaster II.

The Foundation of Medieval Genealogy provides all that is known of Gilbert FitzRoger FitzReinfrid’s ancestry, which is only two generations.

Roger FitzReinfrid Lord of Kendal m unknown

~ Gilbert FitzRoger FitzReinfrid dbef 1220 m 1184/89 Hawise de Lancaster (above).

~ ~ William de Lancaster dc 1247 m Agnes de Brus

~ ~ daughter m Roger de Kirkeby

~ ~ Hawise de Lancaster m Peter (III) de Brus, Lord of Skelton, son/Peter de Brus (II)

~ ~ Alice de Lancaster dbef 1247 m 1220 William de Lindsay, son/Walter de Lindsay

~ ~ Serota de Lancaster m Alan de Multon

Wikipedia’s article, the Barony of Kendal, makes William de Lancaster I the first true Baron of Kendal, i.e.

Ivo de Taillebois d 1094 m 2ndly Lucy d 1138, dau[niece]/Thorold of Lincolnshire

~ daughter m Eldred

~ ~ Goditha m Gilbert de Lancaster, son/unknown

~ ~ ~ William “Taillebois” de Lancaster, Baron of Kendal, fl 1166

That article’s author cites William Farrer, co-editor with John F Curwen of the Records relating to the Barony of Kendale which 3 volumes were published in 1923. Since these are available at British History Online, we’ll go to source.

In the Introduction of volume 1, Farrer defines the area which in 11th and 12th centuries was covered by Kentdale . . .

“. . . in that part of North-Western England, which had lain within the power sometimes of the earls of Northumbria and sometimes of the earls of Mercia . . .”

As proof of its Danelaw connections (and this is relevant to our quest) Farrer cites the system of assessment by ploughlands or carucates, as seen in the Domesday Book, which are peculiar to Danelaw and which here overlies the earlier system of English hides.

As further evidence, the northern half of this region, known as “Westmaringaland” would later be divided into East, Middle and West wards, thus echoing the three-way land divisions found elsewhere in Danelaw, e.g. the Ridings of Yorkshire and Lindsey. The land south and seaward of “Westmaringaland” shows two such three-way divisions: Amounderness, Lonsdale, Kentdale, Cartmel, Furness and Copeland.

Ivo de Taillebois received the grant of Kentdale, Beetham and Kirkby Stephen. When he died circa 1097, his widow Lucy, who Farrer makes daughter of Thorold of Angers, then married Roger Fitz-Gerold (Roger de Romar the son of Gerald de Romar, as given by The Foundation of Medieval Genealogy).

It might be expected that this Fitz-Gerold and his heirs would succeed to Ivo’s possession of Kentdale but this wasn’t so – or at least there’s no evidence of it. Instead, it seems that Kentdale returned to the crown – until Henry I (1100-35) gave almost the entirety of the region to Nigel d’Aubigny. Though there’s no surviving document-evidence for this either.

Around the year 1114, Henry I granted the honour of Lancaster (“Twixt Ribble and Mersey”), late the hold of Roger de Poitou, to his nephew Stephen of Blois, later King Stephen. Included in this grant was the region of Kentdale. So it seems Nigel d’Aubigny held Kentdale as sub-tenant only. And if Nigel d’Aubigny held as such, it seems likely that so too did Ivo de Taillebois.

In short, so far we find the sub-tenants; we do not find the tenants-in-chief and it is those we seek.

Nigel d’Aubigny died in 1129. His son and heir, Roger de Mowbray, then being a minor of 11 or so years, the vast estate forming the d’Aubigny’s inheritance was taken into the king’s wardship. We know this, for the estate’s many parts were listed in the Pipe Roll of that year. Yet there is no mention of Kentdalin in that Pipe Roll. Neither is Kentdale included in “Westmaringaland” which at that time was in the king’s hands.

But if Kentdale was not in the king’s hands, where was it?

The following reign, of King Stephen (1135-1154), generally presents the local historian with an unfathomable black hole devoid of evidence. Not only did Stephen abuse the land and tenants entrusted to him, his reign was marked by constant warring. That’s never a good time for the keeping of records – they tend to char when the castles and manor-houses are fired. However, a charter was issued between 1145–1154 by Roger de Mowbray, now of age, which enfeoffed a certain knight “of his land of Lonsdale, Kentdale and Horton in Ribblesdale, to hold by the service of four knights”. Said knight was William de Lancaster, son of Gilbert and his wife Goditha.

Goditha, you’ll remember, was granddaughter of Ivo de Taillebois and Lucy niece of Thorold of Lincolnshire and/or Angers.Her husband, though termed ‘de Lancaster’ was son of unknown.

The terms of the grant weren’t to last long, for the entire area of Cumberland, as far south as beyond the Ribble and into Lancashire, was soon in the hands of David, king of Scotland. David I granted the whole of Westmaringaland to Hugh de Morville. This name might seem familiar; we’ll come to that later. As yet, Hugh de Morville was the king of Scotland’s closest friend and later would become Constable of Scotland.

But, despite the change of kings and overlords, William de Lancaster still held land in Westmarieland and Kentdale – just now he held them of Hugh de Morville instead of de Mowbray. And he continued to hold of Hugh de Morville even after Henry II had ousted the Scots from Cumberland. For despite he had served the Scottish king, who anyway was great-uncle to Henry II . . .

St Margaret of Scotland, sister to Edgar Atheling of Wessex m Malcolm III of Scotland

~ David I of Scotland b 1084

~ Maud aka Edith b 1080 m Henry I b 1068

~ ~ Mathilda (Holy Roman Empress) b 1102 m 2ndly Geoffrey de Anjou dc 1151

~ ~ ~ Henry II b 1133 d 1189

Henry II adopted Hugh de Morville as a favourite, and granted him continued possession of Westmarieland.

Hugh de Morville

When, circa 1106, Henry I of England gave the Cotentin Peninsula in Normandy to his brother-in-law David, future king of Scotland, Hugh de Morville, resident of the area, joined the future king’s household. Thus Hugh travelled to England with the household when, in 1113, David married Maud, daughter of the English Waltheof (whose involvement with the Three Earls’ Rebellion of 1075 had earned him an emasculating death), and heiress of the earldom of Huntingdon and Northampton. David, inheriting the earldom, granted to Hugh a couple of his manors. He was later to grant Hugh the baronies of Lauderdale and Cunningham in Scotland, as well as the lordship of the greater part of Westmorland.

Hugh de Morville died in 1162. His son Richard succeeded him, not only to the lordship of Westmorland but also as Constable of Scotland. Richard, as we’ve seen, married Avice, or Hawise, daughter of William de Lancaster I.

When in 1170 William de Lancaster died, Richard made promise of 200 marks to Henry II for the right to claim his wife’s lands – but those lands were in Lancaster, not in Kentdale. Other lands of Richard and Hawise mentioned in charters are found likewise to be in Lancaster, not in Kentdale. The boundaries of Lancaster and Kentdale had changed, fixed for all time by royal confirmation during the first decade of Henry II’s rule (1154-1164).

William de Lancaster

In 1174 the borderlands of Cumberland were again in Scottish hands. Though briefly. For on 13 July, 1174, William the Lion, King of the Scots 1165-1214, was defeated and captured at Alnwick by troops led by Ranulf de Glanvill – and Westmarieland was taken into Henry II’s hands. For the next few years William de Lancaster’s former lands were held by an official of the crown. No name is given.

William de Lancaster II was son of William “Taillebois” de Lancaster by his second wife, Gundred daughter of the Earl de Warenne. These are names we need to remember.

William “Taillebois” de Lancaster m 2ndly Gundred de Warenne

~ William de Lancaster II fl 1156 d 1184 m Helewise, dau/Robert de Stuteville

~ ~ Hawise de Lancaster m 1184-89 Gilbert FitzRoger FitzReinfrid Lord of Kendal

William de Lancaster II died in 1184, leaving an only daughter, a precious heiress, Helewise or Alice or Hawise or Avice or other variations. Her wardship was given to William Marshal, Earl of Pembroke. Marshal gave her in marriage to Gilbert FitzRoger FitzReinfrid, son of his steward, along with her entire inheritance which included the land of Westmarieland and Kentdale. Richard I the Lionheart confirmed the grant at Rouen on 20 July, 1189.

King Richard further granted to Gilbert . . .

“. . . his whole forest of Westmarieland, Kentdale and Furness, to hold as fully as William de Lancaster I had held it and by the same bounds, together with the forest in Kentdale that he had given to Gilbert, with six librates of land, to hold in as beneficial a manner as Nigel de Aubigny had ever held it; further that what was “waste” in the woods of Westmarieland and Kentdale, in the time of William de Lancaster I, should be “waste” still, excepting purpresture (i.e. encroachment or improvements) made by the licence and with the consent of the lords of the fee of Kentdale and Westmarieland . . .”

From: Introduction, Records relating to the Barony of Kendale:

volume 1 (1923), pp. VII-XVII

William de Lancaster III

William de Lancaster III was son and heir of Hawise de Lancaster and Gilbert FitzRoger FitzReinfrid.

In 1225, Henry III (1216-1272) addressed to him the following letter:

“. . . We have heard grave complaint on the part of the knights and true men of the county of Westmarieland that, whereas we granted and commanded with all of our realm that all the woods, except our own demesne woods, should be disafforested which were afforested by King Henry II, our grandfather, or King Richard, our uncle, or King John, our father, since the time of the first coronation of the said King Henry, our grandfather, and in the charter of that liberty was contained that as we held ourself towards our own dependents, so our magnates should hold themselves towards theirs; you nevertheless hold as forest in the same state as they formerly were certain woodlands and moors afforested since the time abovestated, to the injury and loss of knights and others, your true men and neighbours. Wherefore we command and firmly enjoin that you permit the said woodlands afforested since the aforesaid time to beholden disafforested in accordance with the tenour of our said charter above expressed; so doing in that behalf lest, if you act otherwise, repeated and more serious complaint thereof be borne to our ears. Witness the King, at Westminster on June 30th, 1225 . . .”

Legal jargon never changes. A letter soiked in similar terms was sent to Robert de Vieuxpont, lord of Appleby, Appleby being the name for what was to be the barony of Westmorland.

From: Introduction, Records relating to the Barony of Kendale:

volume 1 (1923), pp. VII-XVII.

Another charter was issued by Richard I in 1189, wherein he granted to Gilbert FitzReinfrid certain crown estates in Kentdale, and coincidently revealed that in the time of Henry II the lords of Kentdale merely held their land of the lord of Appleby. This charter allows us an interesting glimpse of who held what and where.

Quoting from: Introduction, Records relating to the Barony of Kendale:

volume 1 (1923), pp. VII-XVII.

- Over Levens, where the Hall stands, was granted by William de Lancaster II to Norman de Redman with the reservation of the fishery in the Kent.

- The “de Bethum” family held the major part of Farleton and Beetham, and in John’s reign were possessors of the fishery between Arnside and Blawith.

- Gospatric son of Orm and his son, Thomas, held the major part of Preston Patrick and Holme

- Patrick de Culwen, or Curwen, younger brother and eventually heir of Thomas, gave his name to the former place.

- Lands in Burton in Kentdale and Lupton were held early in the 13th century by the “De Burton” family.

How pleasing it would be to find such a charter relating to Robert de Watheby.Though we’re now very close to discovering who was his overlord.

Though the de Lancasters had held Kentdale of Hugh de Morville, they had never been barons. Yet through the process of various grants made during the reign of Richard I (1189-1199), Gilbert FitzReinfrid finally made it to baronial status – i.e. as tenant-in-chief. The lands he held in Kentdale, fixed at the service of a meagre two knights, were the very lands which pre-Hastings had been held by Thorfinnr and Earl Tosti.

To quote Farrer’s in summary, which is given in clipped form by the Wikipedia article:

- no barony or reputed barony of Kentdale existed prior to the grants of 1189–90

- neither William de Lancaster son of Gilbert, nor William de Lancaster II, his son and successor, can rightly be described as “baron” of Kentdale.

- Westmarieland was in the hands of Hugh de Morville by grant of Henry II down to Michaelmas 1176 when it was taken into the king’s hands

- during this time “Noutgeld” [what amounts to a rent] . . . was paid to Hugh de Morville and received by him as part of the issues of his land of Westmarieland

- It appears therefore improbable, if not impossible, that Kentdale was held by barony prior to 1190.

- That it was a barony after that date is proved by . . . the Pipe Roll for “Lancastre” of 5 Henry III (1221)

From: Introduction, Records relating to the Barony of Kendale:

volume 1 (1923), pp. VII-XVII.

Thus there can be no denying who was the big man in this particular part of Cumberland. If Robert de Watheby held here, then he held either of William de Lancaster, and he of Hugh de Morville; or he held direct of de Morville. He could not have been a tenant-in-chief.

Westmarieland or the Barony of Appleby

So much for the precursor of the barony of Kendal. But Watheby (or Waitby as it is now) and Warcop are in the northern barony, that of Appleby, or Westmorland.

The Introduction to The Later Records relating to North Westmorland: or the Barony of Appleby is considerably shorter than that to the Barony of Kendal. It begins with Henry II, who enfeoffed Hugh de Morville, as we have seen. It skips lightly over the expulsion of the same knight who, though not mentioned in the previous account of him, was one of the four who spilled the brains of Archbishop Becket on 29 December, 1170 and made of the man a saint. Though, oddly, this wasn’t the reason for de Morville’s expulsion. It was that he had aided the Scottish invasions and Northern Rising of 1173–74.

In 1179 Henry II granted the honour of Westmarieland to his chief justice, Ranulph de Glanville, he who had led the charge at Alnwick. But he too was deprived of it, this time by Richard 1 in 1190. The Crown again resumed possession.

Next, in 1203 King John granted . . .

“Appleby and Brough with all their appendages with the bailiwick and the rent of the county with the services of all tenants (not holding of the king by military service) to hold by the service of four knights . . .”

From: North Westmorland: The barony of Appleby,

The Later Records relating to North Westmorland:

or the Barony of Appleby

(1932)

Although this is given as evidence of when military service first was due from Appleby/Westmarieland, thus making it a barony, yet it’s of interest to us because of the recipent of the grant. Robert de Vieuxpont.

The author and editor, John F. Curwen (Farrer being now deceased) continues . . .

“. . . the lordship passed down from Robert de Veteripont to his great grand-daughter, Isabella, who married Roger de Clifford in 1269; and from them it passed down through twelve generations to Lady Anne Clifford whose daughter, Margaret, married John Tufton, 2nd Earl of Thanet in 1629 . . .”

I think we can safely say that Robert de Veteripont (Vieuxpont) was overlord to Robert de Watheby’s heirs, at least during the years 1203 to 1228. But that covers only the period from Sir Hugh or Hubert Fitz-Jernegan’s death in 1203, to midway through the life of his son, Sir Hubert, who died in 1239. This is not the most satisfactory of answers.

And, as Copinger tells us in his Manors of Suffolk, Vol VII this same Robert de Vieuxpont was granted wardship of Jernegan’s lands, widow and children. It could be time to look at this from a different angle.

Maud, daughter of Torphin de Watheby

Maud was heir to her father Torphin. There is no problem there, except one asks what of her sister Agnes. It was usual, while an inheritance passed intact to the eldest surviving son (see Gentry Game), if no such son existed then the inheritance was shared between daughters. So one must assume that Agnes got her share too – which didn’t included Wathe manor, in North Cove, Suffolk. Perhaps Maud was given this as convenient to her Suffolk-based husband. Though, as we shall see, there is ample evidence of the Gernegan family, now given the harder Yorkshire ‘G’, holding lands ‘up north’.

A History of the County of York North Riding: Volume 1, published 1914, editor William Page, is available at British History Online. This is another wonderful resource for local historians; most of the parish articles here include lists of placenames found in earlier centuries but now lost. For our first stop – Manfield, a village lying close-to, yet a safe distance from, the Roman-built Watling Street – these 12th and 13th century place-names include:

Buttrethorn

Staynhoudalesike

Waredhou

Lathegarthmire

and Standandestaynecrosse

Pinkney Carr is mentioned in 1717. While in Cliffe, a small village included in the Manfield parish, are found :

Haverfield

Willow Pound

Stonebridge-fields

Scroggy Pasture [love that one]

Lime Kill-fields

and Carlberry.

From: Parishes: Manfield,

A History of the County of York North Riding: Volume 1

(1914), pp. 186-190.

In 1086 Manfield was in the soke of Count Alan’s manor of Gilling. It was part of the honour of Richmond, and so it remained through the centuries.

Sometime before 1137 Count Stephen, younger brother of above Count Alan (see Foundation 2, the Manor), had enfeoffed one Hermer of Kelfield as under-tenant at Manfield. Hermer was succeeded by his daughter Gutherith – Goderida as given in the graphic above.

Torphin son of Robert son of Copsi is the next mentioned, confirmed with his heirs in the tenancy of Manfield at two knights’ fees by Conan IV Earl of Richmond 1146-1171, Duke of Brittany. Hermer and his daughter Goderida are here given as ancestors of Torphin, though bluntly, without more explanation. But we’ve seen that Goderida married Copsi de Watheby, and thus was grandmother to Torphin.

Interesting things are said of Torphin.

- he was known as Torphin de Manfield, de Brough and de Watheby. Brough, you’ll note, is in the Barony of Appleby/Westmorland

- he had a station at Richmond Castle, this being between the kitchen and the brewery. This implies he served as butler to the Bretons of Richmond, which in those days was an honoured and trusted position. Wine, drunk by the magnates only, did not come cheap.

- that while he was descended from a previous lord of Manfield, “his claim to this place must have been through his wife, for the two knights’ fees were divided on his death between his daughters (apparently her children) and the descendants of his son Conan.”

- that from 1169 to 1172 Torphin was one of the surveyors of the works of Bowes Castle

- that in 1210-12 he paid 2 marks for his lands in Richmondshire.

- that he had three daughters:

- Parnel.

It is suggest she might be his natural daughter. (Note, she’s not mentioned in the graphic above). Torphin married her to Geoffrey de Bretaneby – of whom I can find no other reference - Agnes

Who became wife of Robert Tailbois of Hurworth. Hurworth lies to the south of Darlington, Manfield to the west; though there’s no great distance between them, yet one is in Yorkshire, the other in Co Durham. The river Tees forms the boundary. - Maud

Who had four successive husbands:- Robert [it’s suggested this is in error and ought to be Hubert]

- Nicholas de Bueles

- Philip de Burgh, given as son of Thomas de Burgh. That’s probably Burgh-by-Sands, near Carlisle, not Burgh Castle on the Suffolk-Norfolk border; though it could be Burgh-le-Marsh in Lincolnshire.

- and John

- Parnel.

- that Agnes and Maud were their father’s heirs and that both were called ‘de Morvill.’

Now that is interesting in view of what we have learned of Westmorland and Kendal.

The author suggests the ‘de Morvill’ is from their mother whose name is otherwise unkown. Apparently, both daughters were granted a share of the church and the mill to St. Agatha’s Abbey. But the author is rather dismissive of Agnes, there being no further evidence of her or her descendants in connection with Manfield. I found mention of her in Kelfield. - that Maud’s son and heir was Gernegan.

- that Gernegan’s heir was his daughter Avis who was still a minor when he died.

- that said heiress Avis was made ward of Robert Marmion whom, it’s believed, she subsequently married.

Robert or another, she did marry into the Marmion family for the family held Manfield for several subsequent generations. They then were succeeded there, as at Tanfield (more anon), by the Greys of Rotherfield.

All this is thoroughly referenced in footnotes; see Parishes: Manfield, A History of the County of York North Riding: Volume 1, pp. 186-190.

When I first passed this way I was seeking the roots of the Jerningham-Jernegan-Gernegan tree. So having scooped what seemed the jackpot, I moved on to further explore the North Riding of Yorkshire. But now we are trying to understand the descent of an inheritance it might be as well to look at the wider connections.

There was another family holding land in Manfield, known in 13th century as the FitzConans and later as the FitzHenrys of Kelfield. As seen in the graphic and gene-chart above, Robert de Watheby was descended on his mother’s side from one Hermer of Kelfield. But what wasn’t shown in the graphic was that Torphin had a son in addition to Robert. Conan. Conan’s son, Henry, held lands in Manfield in 1202. His grandson, also named Henry, is on record as dividing the mill at Manfield with Avice Marmion (see above) and the Abbot of Easby in 1274. By 1282 Torphin’s holdings at Manfield, two knights’ fees, had been inherited jointly by this same grandson Henry and Avice Marmion.

So, to extend the gene-chart for the Watheby family of Manfield:

Archil

~ Copsi de Watheby fl 1146 m Goderida, dau/Hermer, lord of Kelfield & Manfield

~ ~ Robert de Watheby

~ ~ ~ Robert de Warcop

~ ~ ~ Alan de Warcop

~ ~ ~ Torphin de Watheby, lord of Manfield, fl 1210

~ ~ ~ ~ Matilda [Maud] de Morville m Hugh/Hubert, son/Gernegan d 1204

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ Gernegan m Rosamund dbef 1215

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ Avice dc 1284 m Robert Marmion d 1240

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ Nicholas

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ Hugh

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ Isabel

~ ~ ~ ~ Agnes m x3

~ ~ ~ ~ Robert d w/o issue

~ ~ ~ ~ Conan de Manfield and Kelfield

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ Henry Fitz Conan fl 1202

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ Henry FitzHenry fl 1274

This clearly shows Torphin’s heirs, at least for Manfield, to have been Maud and Conan; and Maud’s heir to have been Gernegan, not Hugh.

The FitzHenrys of Kelfield continued to hold here as mesne lords until 1496. Unlike Wathe and Somerley Town in Suffolk, this was not land held in-chief of the crown, but held of the honour of Richmond.

The Gernegan family held several manors in North Ridings of Yorkshire.

For example in A History of the County of York North Riding, Volume 1 West Tanfield, pp. 384-389 we find Hugh son of Gernegan as tenant of two and a half fees. He is described as a contemporary of Torphin de Manfield and husband of Maud de Morvill, one of the heirs of Torphin de Manfield. And again we’re told that their son Gernegan succeeded to Maud’s inheritance, but nothing is said of their Suffolk-based son, Sir Hubert of Horham.

This is the second mention of Torphin’s daughter and heir being Maud de Morvill, and we’ve already seen that Hugh de Morvill held land that was to become the barony of Appleby or Westmorland, first of David I king of Scotland, and later of Henry II. Since Hugh died 1182, it’s fair to say that Robert son of Copsi, and Torphin too held the manor of Watheby direct of him. In fact, the author of Records relating to the Barony of Kendale: volume 2 Casterton, pp. 326-340, is quite certain that in the 12th century the lords of Manfield in Yorkshire, and of Waitby and Warcop in Westmorland, i.e. Copsi, Robert and Torphin, were lords in Casterton too. To quote:

“. . . [in 1222] Nicholas de Buelles and Matilda [Maud] his wife, one of the daughters and eventually co-heirs of Torphin son of Robert de Manfield, granted for themselves and Matilda’s heirs to Alice [Helewise] daughter of Gilbert, the tenant, a moiety of the manor of Casterton for 30 marks and a palfrey. This Alice, daughter of Gilbert, was undoubtedly the daughter of Gilbert Fitz-Reinfrid and sister of William de Lancaster III. Before the year 1235 she married William de Lindesay and in that year he and Alice his wife called William de Lancaster to warrant to them concerning the third part of the mill in Casterton . . .”

If I’m reading this right then Alice, daughter of Gilbert Fitz-Reinfrid, held land of Maud de Manfield, aka de Morvill.

When we first looked at The Later Records relating to North Westmorland: or the Barony of Appleby, we went only as far as Robert de Vieuxpont who held the lordship from 1203 till his death in 1228. The lordship remained in his family, till his great-granddaughter, Isabella, who in 1269 married Roger de Clifford. The lordship then passed to the Cliffords.

That account continues, moving now to the Barony of Kentdale

“. . . it would appear that the lordship over it had been taken from Roger de Mowbray, at or before the accession of Henry II, and united to Westmarieland as a mesne lordship held by the service of £14. 6s. 3d. for noutgeld. So that the Williams de Lancaster, the first and the second, were ipso facto tenants of Hugh de Morvill . . .”

My italics.

To repeat:

“The lordship remained in his family, till his great-granddaughter, Isabella, who in 1269 married Roger de Clifford.”

To connect the dots: if Alice de Lancaster held Casterton of Maud de Watheby, aka Maud de Morvill, it seems quite certain that said Maud de Morvill was heir to Hugh de Morvill. A child could reason it.

So now we can answer from whom did Maud de Watheby hold the manor of Wathe. If she was the heir to Hugh de Morvill then the answer must be of the king as tenant-in-chief.

But wouldn’t that destroy our story of how the manor passed out of Sir Jernegan’s hands and into those of Roger FitzOsbert?

So let’s first make sure that Maud de Watheby really was heir to Hugh de Morvill.

The Later Records relating to North Westmorland: or the Barony of Appleby, being the later records are by no means thorough in their coverage of the earlier centuries. However, in St Laurence, Crosby Ravensworth we find this.

Mauld’s Meaburn Hall

“. . . King’s Meaburn and Mauld’s Meaburn were anciently one manor and continued undivided until the time of Hugh de Morville’s rebellion in 1173–4. The king then escheated the manor, saving a portion which was allowed to remain to de Moreville’s only daughter, Maud. Maud married William de Veteripont [Vieuxpont] and about 1230 Ivo de Veteripont granted to his daughter, Joan, for her homage and service one toft with a croft . . .”

Maud daughter of Hugh de Morvill married William de Vieuxpont.

“The King . . . granted the lordship of all [Sir Hubert Jernegan’s] large possessions, and the marriage of his wife and children to Robert de Veteri Pont or Vipont, so that he married them without disparagement to their fortunes . . ”

From Manors of Suffolk, Vol VII, W A Copinger

Manor of Wathe or Wade Hall or Woodhall

Sir Hubert Jernegan’s mother was Maud de Watheby, aka de Morvill. But was she the same Maud, daughter of Hugh de Morvill who had married William de Vieuxpont?

When Hugh de Morville died in 1162, he was succeeded both as Constable of Scotland and in his English and Scottish estates by his son Richard. His English estate was quite extensive, including manors in Northamptonshire, Rutland, and Huntingdon, and of course, the barony of Westmorland and part of Kentdale.

Hugh de Morville d 1162

~ Richard de Morville d 1189 m Avice (Alice, Hawise) de Lancaster

~ ~ William de Morville fl 1180, d w/o issue

~ ~ Malcolm de Morville – killed while hunting

~ ~ Maud de Morville m William de Vieuxpont, Lord of Westmorland

~ ~ Elena de Morville bc 1170 m Roland of Galloway

From Wikipedia’s article on Richard de Morville

According to that article, it was Elena, not Maud, who was the “eventual sole heir” to her father Richard.

But in the article on Hugh de Morville we find there were two Hugh de Morville’s, father and son, and that the Hugh de Morville who co-assassinated Thomas Becket was Hugh the son. See Gene-chart below.

It was this same Hugh de Morville, the son, who later (1174) forfeited the Lordship of Westmorland, inherited from Hugh de Morville the father. Said land and lordship of Westmorland then was granted to Maud, his sister, the same Maud who married William de Vieuxpont.

Yet Wikipedia’s article on Richard de Morville gives this Maud who married William de Vieuxpont as daughter of Richard and thus niece of Hugh, the son of Hugh de Morville. With such conflicting statements we are entitled to be confused.

Hugh de Morville d 1162 m Beatrice, dau-heir/Robert de Beauchamp

~ Hugh de Morville, Lord of Westmorland (the assassin or Thomas Becket)

~ Maud de Morville m William de Vieuxpont.

~ Richard de Morville d 1189 m Avice (Alice, Hawise) de Lancaster

~ Ada de Morville m Roger Bertram, Lord of Mitford, Northumberland

~ Simon de Moreville d 1167, of Kirkoswald, m Ada de Engaine

I checked this genealogy against that given by the Foundation for Medieval Genealogy

Hugh de Morville d 1162 m Beatrice de Beauchamp

~ Hugh de Morville daf 1153

~ Richard de Morville d 1189, heir to Hugh his brother m aft 1155 Hawise de Lancaster, widow/William Peverel (disputed by FMG)

~ ~ William de Morville d 1196 m unknown

~ ~ Helen de Morville d 1217 m Roland Lord of Galloway

~ Malcolm de Morville

~ Ada de Morville dc 1227 m 1stly Richard de Lucy

~ Ada de Morville dc 1227 m 2ndly as 2nd wife, Thomas de Multon

~ Joan de Morville m Richard Gernon

Maud de Morville is absent from FMG, both as sister of Richard de Morville, and as daughter. This doesn’t mean she didn’t exist, only that her name doesn’t feature with others of the family in any of the surviving charters.

So back to the Hugh de Morville article in Wikipedia; what are the sources? Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Stringer (2004). Unfortunately the DNB requires subscription to access The article on Richard de Morville cites the same DNB, though not specifically in reference to Maud, sister or daughter.

However, Wikipedia’s article on Robert de Vieuxpont repeats of Maud de Morville as wife William de Vieuxpont, she being mother of Robert. Here, in ‘References’ is a link to a ‘Biography, of Robert de Vieuxpont in service of King John 1203’ To quote:

“Vieuxpont [Veteri Ponte, Vipont], Robert de (d. 1228), administrator and magnate . . . was the younger son of William de Vieuxpont (d. in or before 1203), who became an important Anglo-Scottish landowner, and his wife, Maud de Morville (d. c.1210), whose father Hugh (in 1170 one of the assassins of Thomas Becket) forfeited the barony of Westmorland in 1173 . .

“. . . in February 1203 he was given custody of the castles of Appleby and Brough, to which the lordship of Westmorland was added a month later; then in October 1203 custody during pleasure was changed to a grant in fee simple, for the service of four knights, and Vieuxpont had become one of the leading barons in northern England.”

Sources? Well, while the author provides an impressive list he doesn’t note which belongs to what.

The other link given as ‘References’ is to Westmorland Barony, an informative site that covers the history of Barony of Appleby from 1066.

“. . . William the Norman Conqueror gave the whole of Cumberland, and this great barony, to Ranulph de Meschiens, who married Lucia, the sister of Hugh Lupus, Earl of Chester . . .”

Ranulph de Meschiens and Lucia had a son Ranulph, heir to all but a large portion of Cumberland which had previously been granted to “his uncle William and others”.

When Ranulph de Meschiens, junior, became Earl of Chester he gave the barony of Appleby to his sister, wife of Robert d’Estrivers, or Trevers. Their daughter married Ranulph Engain, who thus was the next to acquire the barony. Ranulph Engain’s granddaughter “passed it to Simon de Morville”, assumingly through marriage. And Simon de Morville’s son Hugh was one of the four knights that assassinated Thomas-a-Becket, Archbishop of Canterbury.

Wrong – or at least, not unless Simon de Morville was alias Hugh de Morville the elder. Wrong too that the king seized his estates in reaction to the assassination. As we’ve already seen, Hugh de Morvill lost his hold of Westmorland/Appleby because of his involvement with a northern rebellion.

“. . . the barony then was retained by the crown till King John granted it to Robert de Veteripont, (Lord of Curvaville, in Normandy), together with the custody of the castles of Appleby and Brough, and the “Sheriffwick and rent of the county of Westmorland,” in perpetuity . . .”

From Westmorland Barony.

In 1228 John de Vieuxpont succeeded his father Robert as sheriff of Westmorland. In 1242 John’s son and heir, Robert de Vieuxpont, being a minor was taken into the king’s wardship. He later joined the barons in rebellion against Henry III and died in 1264 of his wounds. The barony was subsequently restored to his daughters Isabella and Idonea.

This might seem an improvement, for now we have certain evidence of a Robert de Vieuxpont alive at the time of Sir Hubert Jernegan’s death. Yet he was an infant.

And the source for the above history? None is given.

Returning to Wikipedia, what are we told about William de Vieuxpont? After all, he was the one who married Maud de Morville.

“. . . William de Vieuxpont, Lord of Westmorland married Maud, daughter of Richard de Morville (1189-?). She died in 1210. He died in 1203 . . ”

And the source? The Oxford National Dictionary of Biographies.

So Maud was daughter of Richard de Morville, not his sister. But this Maud de Morville, who married William de Vieuxpont, could not be the same Maud de Morville, daughter of Torphin de Watheby. She is already the daughter of Richard de Morville. Yet she could be the unnamed wife of Torphin and mother of Hugh fitz Gernegan’s wife, Maud de Morville.

Alice de Lancaster held Casterton manor of Maud de Watheby, aka Maud de Morvill, aka Maud de Manfield.

But then how could this Maud de Morville have time to marry Torphin and produce, at the least, daughters Agnes and Maud, and then for the daughter Maud to marry Hugh fitz Gernegan, when said Hugh fitz Gernegan died in 1203 – and so too did Maud de Morville’s first husband, William de Vieuxpont.

The answer is twofold:

- we – and the authors of these histories – are looking at the evidence from a future perspective and this causes distortion in the sequence of events. i.e. a woman might be widowed and remarried ten, even twenty, years after her daughter has married and produced five or so grandchildren. Which leads to the second part of the answer.

- Agnes and Maud were not Thorpin’s daughters. It clearly says that in the History of the County of York North Riding; Manfield

“. . . the two knights’ fees were divided on [Torphin’s] death between his daughters (apparently her children) and the descendants of his son Conan . . .”

My italics, but not my brackets.

And that is why Robert, who died without issue, is shown on the Casterton graphic, and why Conan is not.

And that is why Agnes and Maud/Matilda are shown on the Casterton graphic, but their step-sister Parnel is not.

So to amend and update the Manfield gene-chart:

Archil

~ Copsi de Watheby fl 1146 m Goderida, dau/Hermer, lord of Kelfield & Manfield

~ ~ Robert de Watheby

~ ~ ~ Torphin de Watheby, lord of Manfield, fl 1210 m 1stly unknown

~ ~ ~ ~ Parnel

~ ~ ~ ~ Conan de Kelfield

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ Henry FitzConan fl 1202

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ Henry FitzHenry fl 1274

~ ~ ~ Torphin de Watheby, lord of Manfield, fl 1210 m 2ndly Maud de Morville, widow/William de Vieuxpont

~ ~ ~ ~ Robert d w/o issue

Hugh de Morville d 1162 m Beatrice de Beauchamp

~ Hugh de Morville daf 1153

~ Richard de Morville d 1189 m aft 1155 Hawise de Lancaster

~ ~ Maud de Morville m 1stly William de Vieuxpont

~ ~ ~ Agnes m x3

~ ~ ~ Maud de Watheby m 1stly Hugh/Hubert, son/Gernegan d 1204

~ ~ ~ ~ Gernegan m Rosamund dbef 1215

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ Avice dc 1284 m Robert Marmion d 1240

~ ~ ~ ~ Nicholas son of Gernegan

~ ~ ~ ~ Sir Hubert Jernegan dc 1239 m Margery de Herling

~ ~ ~ ~ Isabel

~ ~ Maud de Morville m 2ndly Torphin de Watheby

~ ~ ~ Robert d w/o issue

___________________________

Now we have journeyed north, to North Ridings of Yorkshire, we’re in a better position to find Bryan, the very root of the Jerningham tree. Though Prince of Denmark? That I still doubt. For as I said at the start, Brian is not Danish name. It was a name common amongst Bretons of this period, as much as was Conan and Alan. And at this period in the North Riding of Yorkshire Bretons abounded.

But word-counts and deadlines have again tripped me. I have just enough time to add this, then the rest must wait for next week.

We have seen how, in the account of Wathe Manor in Copinger’s Manors of Suffolk, the names given in the early part all have northern providence. Robert de Watheby and his daughter Maud, Robert de Vieuxpont. Even the Jernegan family are represented in the north. And I have said of the name of the manor, that it’s formed upon wade, and is a name found in many places, north to south, throughout England.

Wathe – the wading-place

“At the east end of Hurworth village there is another bridge across the Tees, and there are fords near Neasham village called High Wath and Low Wath . . .”

From A History of the County of Durham:

Volume 3 (1928), Hurworth, pp. 285-293

Wath, or Wathe, a wading-place. Some have grown to be villages.

Wath St Mary:

“. . . a parish, partly in the wapentake of Allertonshire, and partly in that of Hallikeld, N. riding of York; containing, with the townships of Melmerby, Middleton-Quernhow, and Norton Conyers . . . “

Wath:

“ . . . a township, in the parish of Hovingham, union of Malton, wapentake of Ryedale, N. riding of York, 8 miles (W. by N.) from Malton . . . “

Wath-Upon-Dearne (All Saints):

“. . . a parish, in the union of Rotherham, N. division of the wapentake of Strafforth and Tickhill, W. riding of York . . .”

From A Topographical Dictionary of England (1848), pp. 486-490.

But to return to the parish of Wath that straddles the Allerton and Hallikeld wapentakes in the North Riding of Yorkshire, which in 1831 comprised the township of Wath and the chapelries of Melmerby, Middleton Quernhow and Norton Conyers . . .

The manor of Wath had been held, pre-Hastings, by Archil and Roschil. Archil the father of Copsi, already met in the Casterton graphic. By 1086 the manor had become part of Count Alan’s extensive honour. And so it remained, held of the Bretons of Richmond down through the centuries.

But there is an interesting story told here. It seems the whole of Wath and the church were granted, before 1156, to the abbey of Mont St. Michel. Yet, almost as if he didn’t know, Alan III, Lord of Richmond, went ahead and granted the land to Brian, lord of Bedale.

“. . . and that Brian or his son enfeoffed of it one of the ancestors of the Marmions, probably Gernegan son of Hugh, against whom the monks of Mont St. Michel brought a plea concerning land in Wath in 1176-7 . . .”

To compound the matter, a few years previous, Brian, younger brother of Conan IV, Earl of Richmond, Duke of Brittany (1146-1171) had confirmed his predecessor’s grant to the abbey. The monks were not about to settle quietly out of court and the dispute rolled on for some sixty years. It came to a head in 1239 when the monks took it to the Papal Court.

The abbey claimed they’d always had two monks on the manor. (Though how that proves their right I’m sure I don’t know.) Sir Robert Marmion claimed he had it by right of his wife – Avis daughter of Gernegan, who again we have met. Moreover, Sir Robert offered to prove by duel that the manor was his. And, foolishly, the then-abbot accepted.

The duel duly was fought

“ . . . in a place appointed by the king, the knight bringing a multitude of armed men, and the knight’s champion was more than once brought to the ground, on which the knight’s party interfered to rescue him, and threatened death to the abbot and his champion, so that the abbot, fearing that death would ensue, came to the spot and renounced his right, which renunciation the knight would not admit save by way of peace and payment of a sum of money . . .”

From: A History of the County of York North Riding:

Volume 1 (1914), Wath, pp. 390-396.

The rights and wrongs of the case are irrelevant, though it was later judged by the pope that the Marmions did have the right of the claim. What is relevant is that Wath in North Riding of Yorkshirewas held by one Hugh, son of Gernegan the elder, husband of Maud de Watheby. And this at a time when Robert de Vieuxpont was active as a sheriff of the northern reaches – the same Robert de Vieuxpont who was the son of William de Vieuxpont and Maud de Morville, these being Hugh Fitz Gernegan’s in-laws.

I believe there has been a mistake, a perfectly understandable muddling of one place for another. I believe the account we’re given by Copinger and Blomefield belongs to the northern Wath. I believe the Suffolk manor of Wathe to be named merely for the fact of its location, beside the river Waveney at a point that might be waded. I believe that manor was not in Jernegan hands until inherited along with Somerley Town by Sir Peter Jernegan in 1338.

___________________________

And in the next post, finally, we’ll meet with Bryan. But will he be Danish, or Breton?