(Part 11 – Final Part – in the series, Gernegan Case Reopened)

In the previous post, Lost in Lobineau, we looked at the evidence for a possible identification of Jarnigon son of Daniel de Ponte, Lord of Pontchateau with Gernegan I, the high-ranking canon at York abbey, grandfather of Gernegan II of Tanfield, Yorkshire. What we found, while suggestive, was far from conclusive.

So what evidence might we find to support the identification of ‘Rivellonus & Jarnogotus filii Hamelini’ and Jarnogot’s son, Radulphus, featured in the Montfort charter of 1151(see Table 3b, C12th Jarnogon Charters), with the Jarnogot and his son Ralph of Paling in Sussex, c 1158?

From Gernegan 7 of Sussex

A. 11537

“Confirmation by Ralph the second, bishop of Chichester, the king’s chancellor, of a charter whereby Sefrid the second, bishop of Chichester, his predecessor, confirmed to the canons regular of the causeway of Arundel (de Calceto Arundell‘), serving God therein the hostel of the poor of Christ . . .

“ . . . of the gift of Gernagan de Palinges, and by the grant of his son Ralph:—part of their land, as they confirmed it . . . “

‘Deeds: A.11501 – A.11600′, A Descriptive Catalogue of Ancient Deeds: Volume 5 (Dates to 1180 x 1204)

The Rape of Chichester

‘Rogate’

“Gernagod’s holding later became known as the manor of Wenham, described as a member of Harting in 1195, and was held of the Bohuns of Midhurst. Gernagan and his wife Basile gave to the Abbey of Durford Alwin Bulluc and his land. Ralph son of Gernagan gave the abbey the tithes of his mill at Wenham, and on 1195 land of Ralph Gernagan at Wenham was an escheat.”

Geldwin de Bohun’s inheritance

The Gernagods’ holdings are mentioned in the account of Geldwin’s inheritance from his brother Ralph de Bohun (died 1158)

- the fief of Gernagodus of Paling and Horemere

- the land of the manor of Burne, which Gernagodus, William de Chesney, Richard Ruffus and Thomas de Aseville then held

From Stapleton’s ‘Observations’ in Magni Rotuli Scaccarii Normanniae Sub Regibus Angliae, p 31.

Gernegan and his son Ralph had a substantial holding in Sussex, as gleaned from these sources:

- The House of Paling and its land in the borough of Arundel

- The manor of Wenham in Rogate (part of Harting hundred)

- The fief of Paling and Horemere

- A third part of the manor of Burne (in Westbourne).

In the Gernegan Timeline we tentatively identified Gernagod of Harting and Paling with Gernag’t of Stonham and Gernegan I of York and Whitby. But there was nothing in the Sussex sources to firmly date Gernagod; there was only a terminus for his son Ralph.

- Ancient Deed 11537, dated to 1180-1195, is a confirmation of gifts previously made. Ralph son of Gernegan confirms Gernagod’s earlier gift of land. The Deed does not give a date for the father, only for the son.

- In thne Inheritance of Geldwin de Bohun, dated by his brother’s death to 1158, the reference is to the fief of Gernagodus of Paling and Horemere. This neither implies that Gernegan the father is still alive, nor that he’s still in town.

All we can say with certainty is that Ralph was an adult in 1158, and died in 1195. But that at least allows us to construct a simple Gene Chart:

~ Gernegan/Gernagod (fl 1158 ?)

~ ~ Ralph b before 1158, d 1195

In Lost in Lobineau I suggested a Date-of-Birth range for Gernegan I of 1080 x 1090, based on his minimum age when attesting Eye Charter 136 (and the several charters at York), and his death at Whitby in 1160 x 1170. The Montfort Charter, dated to 1151, does not conflict with this DoB.

The evidence thus far:

- Jarnogod and son Ralph in Brittany in 1151.

- Gernagod and son Ralph in Sussex in 1151.

This certainly warrants investigation.

Montfort Charter, 1151

Titres de Montfort

(Lobineau, p153).

“Rivellonus & Jarnogotus filii Hamelini ”

“ Radulphus filius Jarnogoti ”

This data-packed document is a donation charter, a supplement to the Foundation Charter of William de Montfort for his abbey at Montfort-sur-Meu.

This should not be confused with the Norman Montfort-sur-Risle. Nor with the House of Montfort which from 1365 to 1514 supplied the dukes of Brittany (theirs was Montfort de l’Amaury in the Ile de Paris).

Montfort Abbey was founded by William de Gaël-Montfort, of the baronial Gaël-Montfort-Brécilien family that, in C11th, had built Montfort-sur-Meu for its defensive assets – the motte, set on a natural hill, overlooks the rivers Meu and Garun.

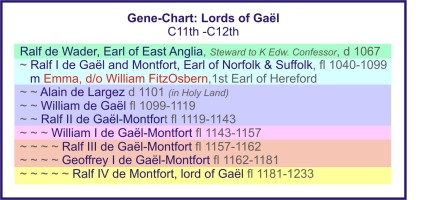

Lords de Gaël-Montfort-Brécilien

We might pause for a moment to consider the roots of William de Gaël-Montfort. He was grandson of Ralf de Gaël, the former earl of Norfolk and Suffolk who was exiled from England in 1075 following his attempted rebellion. Ralf de Gaël was son of Ralf the Staller (steward).

It is thought that Ralf the Staller was amongst the many Bretons and Normans who accompanied the Norman Queen Emma when she came to England as wife of Ætheræd II ‘the Unready’. Ralf remained in England during the turbulent years of Scandinavian rule, and later found favour with Edward the Confessor. In 1066 he supported Duke William of Normandy in his conquest of England – for which he was granted the earldom of East Anglia, made vacant by the death of King Harold’s brother, Earl Gyrth.

Despite Ralf de Gaël inherited his father’s extensive East Anglian estate, with manors in Essex, Cambridgeshire, Lincolnshire, Norfolk and Suffolk, he did not inherit the full extent of his father’s earldom. King William reduced it to Norfolk and Suffolk only. Perhaps this was enough to spark his rebellion in 1075, though his father had died in 1067 and this seems a long time for his resentment to boil. Perhaps it was stirred by another discontented earl who also had not inherited the full extent of his father’s powers: his new brother-in-law, Roger de Breteuil, 2nd Earl of Hereford. (See Revolt of the Earls)

Whatever the cause of rebellion, in King William’s absence it was promptly put down by the warrior bishops, Odo of Bayeux and Geoffrey, bishop of Coutance. Ralf and his followers were forfeit their lands and exiled from England.

Ralf, however, still had his Breton barony of Gaël (see Map below). There he took refuge, out of reach of England’s King William. Yet the following year, 1076, he joined another uprising against the same king, this time in Brittany, led by Duke Hoel.

In retaliation, and concerned for the security of his western border, William besieged the castle of Dol. This was not the first such siege of Dol but almost a repeat of the 1064 siege shown on the Bayeux Tapestry – in which Ralf de Gaël, again, was involved. On that occasion William had had the additional arms of Earl Harold and his men. Now, despite his efforts to take the castle, Dol held. Seeing an opportunity to extend his power, Philippe I king of France intervened on behalf of the Bretons. William raised the siege and fled. It was the Conqueror’s first serious defeat in twenty or more years.

Ralf de Gaël remained a powerful force in Brittany. It was he who built the castle at Montfort before joining the First Crusade where he and his wife Emma and his son Alain died in 1099. He was succeeded by his younger son William. But William died without issue. Thus it was the youngest son Ralf who inherited all – including the Norman honour of Breteuil, inherited from his mother.

1075 did not see an end to Gaël-Montfort’s involvement in England. Amice, daughter of the exiled earl, sister of the new lord de Gaël, was betrothed to Richard, a son of King Henry I. But Richard died young, before they could marry. Instead, in 1119, Amice married Robert de Beaumont, 2nd Earl of Leicester, and supporter of King Stephen in his battle against the claims of King Henry’s Angevin daughter, Empress Matilda. Although not active engaged in England, in Normandy Robert de Beaumont was fierce in his fight against the Angevin supporters – for which he lost his Normandy estates. He died in 1167 having served Henry II as Chief Justicar of England and Lord High Steward.

In the seventh century Gaël, then the capital of Dumnonia, was the royal residence of Juthaël and his son St Judicaël and, later, of Erispoë. Set at the centre of a vast forest – Poutrecouët (Porhoët) of which the Forest of Brocéliande is but a small remnant – the royal castle was built on the banks of the Meu, close to today’s town. That same castle was the birthplace of the C11th lords Gaël-Montfort-Brécilien.

The barony of Gaël-Montfort-Brécilien originally included more than 40 parishes, though it has since lost some. (See ‘Liste des seigneurs de Montfort en Bretagne‘ on Wiki Francais). In addition, in 1160 La Gacilly (between Ploërmel and Redon) and its castle belonged to Olivier de Montfort, brother of William de Gaël-Montfort.

The Lands of the Montfort Charter

The full text of the Montfort Charter is given in the Jarnigan Appendix. For our purposes, we need only to know who gave what and where. The charter begins:

“I, William Lord of Montfort, together with others brought to the church of saint Jacob . . .”

William de Montfort’s very long list of gifts begins with what will form a regular annual income. The tithes:

- the tithe of a new mill in Montfort

- the tithe of William’s grain, his vineyards and gardens

- a tenth of his forest at Colum

- half of the rights of way in Monfort

- the sale of bread and wine in Montfort

William then lists the lands he has given . . .

From the land around the town of Gaël:

- the land of Præstebolius

- the land of Charbonel

- the land of Foloheel

- the land of Even and Garner de Noa

- the land of Dodel (Dodeliensium)

- the land of the sons of Rivald de Lande

- the land of the sons of Judicaël son of Moyse

In Faut (which at first I presumed was Illifaut):

- the land of Guillelm

- the land of Bodin

- the land of Albert (Albertensium)

- the land of Finid

- the land of Guillelm the presbyter of Borrigath

- the land of Illis of Bren

- the land of Daniël Candid

- the land of Gerbert of Brengelin

- the land of Helen son of Delese

William also gave to the monks the tithe of both grain and coin from Thalencach and Monterfil towards the cost of feeding guests. Then, too, he gave:

- the village and land of Guinelmor with its appendages in Talensac

- the land adjacent to the forest of Tremelin

- the mill in Romeliac

- the land of Orene de Curia

- the land of Gaufrid son of Gorrand

- and 2 melliferias (honey-farms) that he had bought from Conan Rothaud, son of Guinned

The next groups of lands came from the parish of St Gilles:

- the land of Joanne son of Mein

- the land of Reutadrus

- the land of Guillelm de Mecahc

- the land of Pascherius

- the land of Hungunar

- the land of Urvos

- the land of Judicaël

- the land of Hefred

- the land of Gorrand

- the land of Gaufrid

- the land of Trumel,

- the field (campum) of Even son of Belissent

To all this his wife Amice assented, and his sons and brothers agreed. Although an essential component of any donation, this was also formulaic.

Next, he tells us of the gifts made by his wife and his vassals – to which he had previously agreed (also formulaic).

His wife gave, in addition to the profits from the sale of bread and meat in the town of Gaël:

- in Talencahc, a mill

- in Sentelei, land next to the Bourg

- in Vineis, Gaufrid son of Bino, and his partner

- in the land of Berner, one quarter of the grain

Of his vassals:

- Lehsent, with the consent of his children, gave in Talencahc land next to the forest

- Herve son of Richald, with the consent of his children, gave a field next to the cemetery

- Mentinit son of Hugo, for the soul of his brother, gave land earmarked for building the miller’s house

- In the parish of Mauron, Peter son of Urvo gave his hunting rights in the valley, and in the village of Autbert

- In the bourg of Bretuil, Guillelm the priest gave the same house that William de Montfort had given him

- In Gevret, Joanne son of Trusell, with the consent of his brothers, gave the tithe/a tenth of the fee of Espergat for the soul of his brother Rafred

- In Irrodoir, Gaufrid son of Ulric gave the land of Capella

- In Bedesco, Dualen son of Blanche, with consent of his children and his brother, conceded what rights he had in village of saint-Jacob

- Cornilellus gave the vinery next to the water Modan

- Hubert gave a vinery with his children’s consent

- In Castle Montfort, Daniel Brito gave the houses that were held of the fee of Froald and with everything, offered his own son to the Church.

- In the parish of Collum, Ralf the priest of Paci gave a vinery, his sister Maria also gave to the Church a vinery.

- Ralph and Revellon, sons of Rothard, with agreement of their children, gave three ‘little fourths’ (quarts?) of grain

- Hodia gave her cottage and field with the agreement of her lord and relatives

- Herve the priest of Capella gave land at Secher in Senteleio

- Peter son of Trehored gave the prebendary grain in the land of Brother Eudo Rigid.

- Hugo son of Respet gave whatever hereditary rights he had in Gahelo.

- Herve son of David gave two cottages with a field.

- In Helisaut, Clamarius gave a field with cottage with consent of his lord and children.

- In the parish of Mauron, Guillelm Sellarius (lit. the lecher) gave a field with consent of his children and lord

- Rivellon & Jarnogot, sons of Hamelin, gave a field next to Musterbio (campum juxta Musterbio)

- Ralf son of Jarnogot sold a cottage with field in Cihiledre (casamentum in Cihiledre)

- Trescant son of Tuali with his children gave three cottages with fields in the bourg of saint Laver

- Jarnogod brother of Demorand gave a cottage and field in Fevrer.

- In sancta Magaldo, Gaufrid of Fevrer gave a field, with the consent of his children

- Three sons of Bernard (the monk mentioned in the preface of the charter) gave their tithe

- And two survivors Gauter & Herve yielded their legal rights worth nine shillings

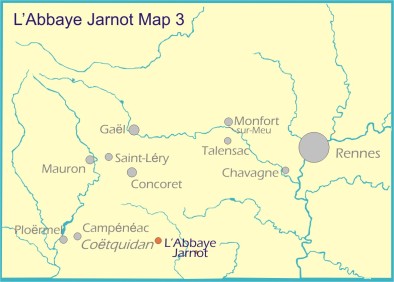

Some of these places can be immediately recognised (See below, Map: Montfort Charter ): Gaël, Talensac, Monterfil, the Forest of Tremelin, Romeliac, St Gilles, Mauron, Bretuil (Breteil), Irrodoir, Bren (Le Bran).

However, it turned out that Faut wasn’t, as I’d first thought, Illifaut; for the lands of Gerbert of Brengelin, Illis of Bren, and Guillelm the presbyter of Borrigath, all listed as lands in Faut, are found much further south, in the parish of Concoret. (See Map Montfort Charter 2)

Other places mentioned in the charter required a more thorough search of a detailed map. I’m not sure the Google Map quite qualified. Despite the ability to zoom into detail, the fuller picture then was lost. It took days to crawl at close quarters across the given area.

There was a problem, too. In the intervening 950 years there have been many changes to placenames. This isn’t only a matter of spelling, for example Bedesc had become Bédée; but some places have suffered a complete change of name. An example is the C11th Brécilien which now is Paimpont. This is where infobretagne.com became an essential to discover the old names, and to confirm my own guesses.

Still, the search was not 100% successful. Yet when we consider that some of these places were not even hamlets – mere fields – at the time of the charter and have long since disappeared, I was delighted to find all but a few of the names. But always my mind was on finding the lands of Rivellon and Jarnogot, sons of Hamelin, and Jarnogot’s son Ralph.

The Results

(See Montfort Charter Map 2 below)

Bedesc: As I have already mentioned, Bedesc now is Bédée, a town north of Montfort, though I could find no outlying village of Saint-Jacob.

Gevret: To the northeast of Bédée and Montfort is Gévezé – or Gevriseio as it is attested in a charter of 1136.

Parish and Forest of Colum: Moving southwest of Montfort is the small town of Le Rocher de Coulon; this is the former ‘Colum’. The forest is now longer evident.

Guinelmor & appendages in Talensac: That this is the land of Guilhermont is confirmed in a summary of the Montfort Charter found on the relevant page of infobretagne.com. The farm of Guilhermont in Talensac was still in existence as late as C18th.

Sancta Magaldo is now St Maugan, formerly part of the parish of Iffendic. Here Gaufrid de Fevrer had a field. Apparently this ‘Geffroy Ferrier ou Fevrier’ was proprietor of the château de Vauferrier. It follows that Jarnogod, brother of Demorand, who gave a cottage and field in Fevrer, lived some place near here.

Vineis: the parochia Campo Vineio was the Latinised version of ‘Chavenne’ or ‘Chaveigne’, the C12th forms of today’s Chavagne.

Sentelei, aka Saint Eloi, is now Montauban-de-Bretagne. William de Montfort’s wife gave land next to the Bourg of Sentelei. Herve the priest, too, gave land at Secher in Senteleio. Also in in terram Santeleio were the lands of Orene de Curia, and of Peter son of Trehored. (infobretagne cites “Dom Morice, Evidence of the History of Brittany, I, col 614″)

The water of Modan: I confess this is a guess. Having looked at the name of every creek, pond and river I then found the C12th Latinised name of Médréac: Modoriacum. So perhaps the vinery that Cornilellus gave was here, in Médréac.

Saint Laver: This is St Lery, whose name is also given as Saint Elocan, Saint Laur, and Saint Livry.

Brengelin: (in Faut) was, in 1151, part of the parish of Concoret.

Borrigath: Today is the tiny hamlet of Boriga; it lies north of Brengelin.

Eleven hits, that isn’t bad. And it leaves only:

Terra Bernerius which might refer to Bernéan, now found as the Bois de Bernéant, part of Coëtquidan, and formerly part of the parish of Campénéac. The name is known from as early as C5th when it was Broon-Ewin or Lisbon Broniwin.

Helisaut. Though we confidently convert this to ‘Helisant’ or ‘Heli-saint’, that doesn’t much help.

So, to map what we have so far:

We are left with ‘the field next to Musterbio’, and ‘a field with cottage at Cihiledre’, i.e. the lands given by Jarnogot and his family. And ‘Gahelo’ in which Hugo son of Respet gave certain rights to the newly-founded abbey, and which I have intentionally left to last.

Gahelo is almost certainly Cahelo. But Cahelo no longer exists (that I can find). However, there is a Rue de Cahelo that runs out of Bellevue. Bellevue lies on eastern the edge of Coëtquidan; it leads directly to l’Abbaye Jarnot.

The Lands of the Sons of Hamelin

Of all the places mentioned in the Montfort charter, Musterbio and Cihiledre, the very places I most want to find, have caused the worst headache. To take Cihiledre first . . .

I found several names that could be today’s version of Cihiledre. The most promising, at first sight, was Lédremeu, in the same area as Champs du Bran, Brangelin and Boriga. This had to be it. But a closer look revealed it wasn’t Lédremeu at all, but L’Édremeuc.

Next favourite was Letra. But some distance southeast of Ploërmel, it was far outside of the Gaël-Montfort-Brécilien lands.

That left Le Lidrio, south of the Forest of Paimpont, on the northwestern rim of Coetquidan, wherein the French military has its training camps. It was the right area. It was close by Bois de Bernéant. But could ‘Lidrio’ possibly evolve from the original Cihiledre?

The other problem with Cihiledre is, in following the Latin ‘in’ it ought to have the ablative ending (generally / -a / -o / -e / -u / depending on which declension). It does end in the ablative / –e /, but it follows the pattern of Latin mater, mother (ablative, matre). And this gives a nominative ‘Cihileder‘. Which would not give us those current placenames that I had found. There is one placename in Brittany remarkably similar: Cléder. But Cléder is way over west, near Roscoff in Finistère.

A different problem existed with Musterbio. It might not look much like the Latin word monasterium but that’s what it is – at least, the Muster- part of it.

In the twelve century Latin was well on its way to becoming French (in this period known as Old French). This involved streamlining the case endings, though not as severely as happened in English in the same period. It also involved the elision of internal consonants. Thus we find, for example, Latin hospitāle becoming Old French (h)ostel. In similar fashion Latin monasterium became Old French muster.

But the placename given for ‘next to Jarnogot’s field’ isn’t just ‘a monastery’; it is a named monastery: Musterbi[o]. But while the spoken Latin was morphing into French, the legal written Church Latin remained unchanged – and juxta (next to) ought to take an accusative ending (-am/-um/-em, depending on declension). In which case the –o ending is wrong. A scribal error, perhaps? A monk who wasn’t so sharp at his Latin declensions (he ought to have had my teacher!). We are left not knowing the correct form for Musterbio.

Today’s Billio was, in earlier times, Moustoir-Billiou. Could this be Jarnogot’s Musterbio? But Billio is 15 miles southwest of Ploërmel, and Ploërmel was part of the county of Porhoët, so we can scrub that suggestion.

Then, while I was map-crawling over the southern extremity of the barony of Gaël-Montfort-Brécilien, I found L’Abbaye Jarnot.

No, it couldn’t be.

Wikipedia, both English and French, were mute on it.

I tried infobretagne.com. On a page titled The Lords of the ancient parish of Guer , with text accredited to Abbé Le Claire, 1915, I found this. (Translation courtesy of Google.)

ABBEY-JARNO

“Tradition tells us that the Abbey-Jarno was a monastery; Cahello, infirmary monks; the Démanchère, the remains of prior; le Verger would be the cloister; Finally this land, at an unknown date, would have belonged to a family Jarno, who left his name.”

La tradition nous dit que l’Abbaye-Jarno était un monastère ; Cahello, l’infirmerie des moines; la Démanchère, la demeure du prieur; le Verger aurait été le cloître ; enfin cette terre, à une date inconnue, aurait appartenue à une famille Jarno, qui lui a laissé son nom.

Note: The Abbaye-Jarno is surely monastic foundation. In 1673, according to Mr. Corson Guillotin, the Priory of Maxent was entitled to justice high on some fiefs in Guer, among others that of the Abbaye-Jarno. From this we may believe that this is the donation of 866 who did give the name of the fief Abbey.

Note : L’Abbaye-Jarno est sûrement de fondation monastique. En 1673, d’après M. Guillotin de Corson, le Prieuré de Maxent avait droit de haute justice sur certains fiefs en Guer, entre autres sur celui de l’Abbaye-Jarno. D’après cela on peut croire que c’est la donation de 866 qui a fait donner à ce fief le nom d’Abbaye.

I further discovered that the abbey was founded by Saint Gurvan, a friend/follower of Saint Samson of Dol fame.

Ca. 1450, the abbey lands were acquired by Jean du Plessis. Today, to quote, again, l’Abbé Le Claire, “the house of the Abbey-Jarno is in ruins, it is a soulless building . . .”

A soulless ruin it might be, but it is also interesting and thought provoking – as was another note I found on the same page:

“In 1588 . . . Perrine Roblot who died of contagion, was the first person buried in the chapel of Saint-Raoul.”

One wonders how old is the town of Saint-Raoul that its first burial was not until 1588.

Pulling out of the zoom, we see how l’Abbaye Jarnot fits with the other places named in the Montfort charter.

The Forests of Gaël-Montfort-Brécilien Region

Paimpont

Coëtquidan and Tremelin

It should not surprise us that the name ‘Jarn’ is found in this area. The abbey is no isolated example. ‘La Grée Gernigon’ lies between Neant-sur-Yvel and Paimpont. And ‘Le Jarnigon’ is found in the Forest of Lanouee, north of Josselin; possibly part of the baronry of Gaël though more belonging to the lordship of Porhoët. There is even an advert for one ‘Gernigon Gerard’, a livestock breeder of Plelan-le-Grand.

This entire region is rich in iron-ore, the forests supplying the necessary charcoal to fire the furnaces. There is archaeological evidence of its exploitation as early as the Hallstatt and early La Tène periods (750-500 BCE). The industry continued throughout the Roman occupation. But it wasn’t until the Late Middle Ages that the iron-working here became a true industry in the modern sense, Finds of accumulated slag and other ferrous waste date to C13th and C14th, totalling more than a thousand tons. Reduction furnaces then are found – a new technique of ore extraction – and the first blast furnace, at the Holly Pond, which dates to late in this period. It seems by C18th there forges were everywhere throughout these forests.

Jarn: as we saw, the name means iron. And where else would the name originate. We have already seen it is an indigenous Gallic name, predating the Romans. Now we can trace it yet further back, to the Late Hallstatt period.

The Forest of Paimpont – or Brécilien as it once was called – is identified today with the magical forest of Brocéliande, wherein Merlin was locked into a cave by the cunning young Vivian, and Arthur drew his magical sword from a stone. An apt setting. And it would have been Jarn’s ancestors who made that sword, literally pulling it out of stone – in the form of iron ore.

Breton Jarnogot, Sussex Gernegod, Suffolk Gernag’t

For the length of a day I felt certain I had found the ancestral land of Jarnigot of Stonham and Harting, this Jarnogot of the Montfort Charter. And then I asked: Does l’Abbé Le Claire give an indication of when l’Abbaye Jarnot was first called that? He says the lands of l’Abbaye Jarnot were acquired, c. 1450, by Jean du Plessis. That implies the previous owner was of the family Jarnot. But he confesses an unknown date for the tenure of Family Jarnot.

Yet, whether we have a correct identification with l’Abbaye Jarnot, or not, we can say with some certainty that Rivellon and Jarnogot, sons of Hamelin, were descendants of the Hallstatt smiths of lived and worked in this great forested region.

Rivellon and Jarnogot, sons of Hamelin, are listed amongst the vassals of William de Gaël-Montfort-Brécilien, and as such cannot be identified with Jarnogon of Pontchateau.

If Jarnogon of Pontchateau is Gernegan I of York and Whitby, and if Jarnogot, son of Hamelin, is Jarnigot of Stonham and Harting, then the northern family must be pronounced separate from that in the south.

But is a coincidence of names sufficient for us to say, yes, this Breton Jarnogot was also the Sussex Gernegod, who in turn was the Suffolk Gernag’t?

Suffolk

As far as Gernag’t of Stonham is concerned, the fact that Ralph de Gaël was Earl of Norfolk and Suffolk until his exile in 1075 and that Jarnogot, son of Hamelin, was a vassal of the lords of Gaël-Montfort-Brécilien weighs heavily in favour of them being the same man.

I personally see it as a distinct possibility that both Iarnagot of Wattisham and Battisford, who we have not discussed in this current post (see Gernegan 5 and 6 of Suffolk) and Gernag’t of Stonham, owe their presence in England to the earlier lord of Gaël.

Iarnagot held land of Eudo fitzSperiwic who was also a Breton and possibly one of de Gaël’s men. The account of the earl’s rebellion says of his men being exiled along with him. But this refers to those involved in his rebellion, not those busily tending their lands. Being exiled, the lands formerly held by Ralf de Gaël were forfeit. The manors de Gaël held as an integral part of his earldom were given to Alan Rufus, Lord of Richmond, who became, in effect if not in title, the new Earl of Norfolk and Suffolk. Other parts of de Gaël’s lands, including those manors inherited from his father who had served Edward the Confessor, were either taken into the king’s custody to be farmed by Godric the Steward or were given to Roger Bigod.

Only three of de Gaël’s followers are named in the Domesday Book: Wihenoc (whose lands were divided between Roger Bigod and Reginald fitzIvo), Eudo fitzClamahoc (whose lands given to Ralph de Beaufour), and Walter de Dol.

At Caldecot in Suffolk, Walter de Dol had possession of a freewoman, Wulfgifu, and her son; Robert Malet, Lord of Eye, received this freewoman with her land.

Also in Suffolk, at Ashfield, Walter de Dol had possession of Snaring the priest when he forfeited his land. The priest, along with other freemen in the area, were given to Ralph de Savenay, Roger Bigod’s man. In Norfolk, Earl Hugh received Walter de Dol’s lands, though some later were given to Roger Bigod..

Robert Malet, Lord of Eye, received freemen in Gislingham, in Suffolk, who, in the reign of King Edward, had been commended to Alsige, nephew of Ralph the Staller, and a thegn of Queen Edith. Roger de Poitou, too, held freemen formerly commended to Ralph the Staller’s neplew Alsige. One assumes these had been part of the rebel earl’s forfeited lands.

The Domesday Book is not all names, numbers and squabbles – though there are plenty of those. Every so often one encounters an explanatory tale. Reginald fitzIvo received Pickenham in Norfolk. This, in the reign of King Edward, had been held by Ralph de Gaël’s father, Ralph the Staller. But in 1075 it was in the hold of Wihenoc.

“A man of Wihenoc’s loved a certain woman on that land and he took her in marriage and afterwards held the land in Wihenoc’s fief without the king’s grant and without livery to him and his successors.”

After the earl’s rebellion, Pickenham (today existing as two villages, North Pickenham and South Pickenham) was distributed between Count Alan, William de Warenne, Reginald fitzIvo, Ralph de Tosny, Berner the crossbowman, and the farm of Godric the Steward.

These are only a few examples yet they illustrate how a man, having followed his lord – in this case, Ralf de Gaël – might then be left behind in England, a tenant, sub-infeudated, to be reassigned to a new lord; perhaps to Eudo fitzSperiwic or to Roger de Poitou. Uniquely informative though Domesday Book is, not every circumstance is explained. We are given a snapshot only of 1086.

Sussex

When it comes to identifying the Breton Jarnogot with the Sussex Gernegod, the evidence is again only suggestive, yet that suggestion is strong. It centres on a family we’ve already met in Sussex, the Bohuns.

But the Bohun family was rooted in the Cotentin region of Normandy; how could they be a link between Jarnogot, son of Hamelin, and Gernegod of Paling and Harting. The answer lies with de Gaël-Montfort’s northern neighbours, the seigneurs de St Aubin d’Aubigny.

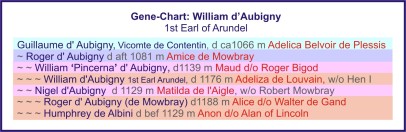

Though these Breton seigneurs share their name with William d’Aubigny who in 1138 became Earl of Arundel when he married Adeliza de Louvain, Henry I’s widow, they were two distinct families. (William d’Aubigny’s family took its name from the village of St Martin d’Aubigny in the Cotentin). To avoid confusion the Breton family is usually named as d’Albini.

Seigneurs de St Aubin d’Aubigny

We find listed in the Liber Vitæ of Thorney abbey…

“Main pater Willelmi de Albinico, Adelisa, Hunfredus de Buun avunculus eius…”

“Main, father of William de Albini, Adelisa, his uncle Humphrey de Bohun . . .”

From Foundation for Medieval Genealogy, quoted in Keats-Rohan ‘Domesday People’

While no date is given, the compilers of fmg suggest that the said ‘Hunfredus de Buun’ is Humphrey II de Bohun. In which case his sister is the Adela named in the 1130 Pipe Roll, a unique document that survives from this period. So we can now complete a gene-chart that shows the Bohun-Albini connection.

It is interesting, and possibly relevant, that William de Albini, son of Main and Adelisa, married Cecily, one of Roger Bigod’s daughter, while William d’Aubigny, father of William 1st Earl of Arundel (and in Sussex, lord to the Bohuns and Gernegods) married Maud, another of Roger Bigod’s daughters. Bigod was, at this time, the newly-made Earl of Norfolk and Suffolk. The d’Aubigny family held extensive lands in Norfolk, with their castle at Old Buckingham. They were founders of Wymondham abbey.

The Norman pillars inside Wymondham Abbey

(founded 1107 by William d’Aubigny)

The church is still in use today.

Main d’Albini held a seigneurial post, which roughly equates to the Norman viscount and Anglo-Saxon (shire-)reeve. As such he held lordship over ‘a dozen parishes’ including Chevaigné, Montreuil-sur-Ille, and Saint-Germain-sur-Ille, which in the 1th and 12th centuries was called Saint-Germain-d’Aubigny.

Yet the Seigneurs d’Aubigny were themselves subject to the Lords Germont, a family which gave its name to Montgermont where they had their castle. In 1152, Montgermont was only a treve in the parish of Pace; it didn’t gain parish status until C13th. It is mentioned in the Cartulary of the Abbey of Saint-Melaine of Rennes: “Pace ecclesiam cum capella Montgermont”. It would seem that the Gaël-Montforts had some connection with Pace since its priest, Ralf, gave his vinery in the parish of Collum to the foundation of Montfort abbey.

‘Montgermont’ was not the only way to spell that name. Amongst the witnesses to a charter (dated 1185) by Henry II’s son Geoffrey who, in marrying Constance, duchess of Brittany, became Earl of Richmond, is one

Guillaume de Montegarniot

(From The Charters of Duchess Constance of Brittany and Her Family, 1171-1221, edited by Judith Everard, Michael C. E. Jones (e-book unavailable)

If this was its original spelling, then we have here another Jarn– family: Monte-garn-iot. Could this be the Jarn-family, the one we seek?

Today, Montgermont is in the canton of Betton. Evidence exists of a settlement at Betton from at least the Iron Age, though documentary evidence dates only as far back as 1138, in the cartulary of the abbey of Saint-Melaine at Rennes. As the compiler of infobretagne.com says:

“The name of this parish from 1152, ‘ecclesiam of monasterio Bettonis’ suggests that a monastery was in place before the monks of the Abbey of Saint-Melaine founded a priory [here].”

Although de Courson suggests the name ‘Betton’ is that of a man, not a locality, and may have belonged to the founder of said monastery, it could also be from the Gallic bedo (pit) or betu (birch) as is given on the same website for Bédée (Bedasco, Bidisco).

Could this monasterio Bettonis (or Bitonis) be Jarnogod’s Musterbi?

In 1155 the castle at Betton was in the hands of Guy de Betton; yet by 1222 it was held by Tison Saint-Gilles, lord of both Saint-Gilles and Betton. St Gilles was part of the Gaël-Montfort barony.

In 1180, an aged canon and treasurer of Rennes, on his death-bed bequeathed to the abbey of Saint-Melaine “deux quartiers et une mine de seigle de rente à prendre dans les dîmes de Gévezé” which Google translates as “two neighbourhoods and a wealth of rye annuity”, to be taken from the tithes of Gévezé.

This canon in question is named as Hamelin Bérenger. He had previously been the priest at Gévezé.

The case is building. Rivellon and Jarnogod, sons of Hamelin, gave at the founding of Montfort abbey a field next to a monastery that could have been the old monastery at Betton. They could have been sons of the priest at Gévezé. They could have been related, a lesser branch, to the lords of Montgermont. They would have been neighbours of the seigneurial family at St-Aubin d’Aubigny whose son William d’Albini-Brit married Adelisa, daughter of the Bohuns of the Cotentin in Normandy who held various lands in England, including in Sussex.

Vassals of the lords of Gael-Montfort who once had held the earldom of Norfolk and Suffolk, a lesser branch of the lords of Montgermont with their connection to the Bohuns: sufficient explanation of how Hamelin’s son Jarnogot became Gernagod of Paling and Harting, and Gernag’t of Stonham. But it offers no explanation of how the same Jarnogot became Gernagot of York. Perhaps that’s because he did not.

The Gernegans of Yorkshire and Suffolk

The Manor of Wathe or Wade Hall

(North Cove, Suffolk)

“This manor was probably called after Robert Watheby, of Cumberland, who held it in the time of Hen. II. From Robert de Watheby the manor passed to his son and heir Thorpine, whose daughter and coheir Maud married Sir Hugh or Hubert Fitz-Jernegan, of Horham Jernegan, Knt., and carried this manor into that family.”

So says W A Copinger in Volume 7 of his ‘Manors of Suffolk’ (1911). But Copinger was only copying Francis Blomefield’s account of the Jerningham family given in his History of Norfolk and today available at British History Online.

“Hugh, or Hubert, son of Jernegan . . . married Maud, daughter and coheir of Thorpine, son of Rob. de Watheby of Westmorland . . . he is mentioned by the name of Hubert de Jernegan, in the Black Book of the Exchequer, published by Mr. Herne at Oxford, 1728, vol. i. p. 301, as one of the Suffolk knights that held of the honour of Eye.”

Even at the time of Copinger’s writing, doubts had been raised as to the veracity of Blomefield’s claim – because it presented too many problems of inheritance, the manor having to pass out of the Jernegan’s keep to be re-acquired later through the marriage of Sir Walter Jernegan to Isabel Fitz Osbert (See Lady Isabel and the Jernegan Lords)

This, the matter of Wade Hall, is the sole documented evidence of a connection between the Yorkshire and the Suffolk Gernegan-Jernegan families. And it dates only to C18th. For though Blomefield’s ‘History’, as published online at BHOL, is dated to 1805, it was written and first published between 1736 and 1745.

Francis Blomefield

Blomefield (1705-1752) died before his ‘History’ was complete, though this had not been a ‘retirement project’. His ambition was to be an antiquary even from his schooldays when his vacations were taken with visiting Norfolk and Suffolk churches (he lived in Thetford, on the county border) to record the monumental inscriptions. This inevitably led to the collection of genealogical and heraldic notes of local families, indulged when he was at college, with Cambridgeshire now his, too, to explore.

So we can imagine the young Blomefield’s delight when, not long after graduating, he was given access to the huge collection gathered and compiled by Peter Le Neve of materials relating to the history of Norfolk.

But Peter Le Neve (1661-1729), was more than Fellow and first President of the Society of Antiquaries of London and Fellow of the Royal Society; in 1704 he was created Norroy King at Arms, i.e. ‘King of the Heralds beyond the Trent’. As such, Le Neve had been responsible for validating the barons and baronets right to bear ‘arms’, which entailed the inspection of supporting evidence. From 1707 to 1721 he was Richmond Herald of Arms.

But more pertinent yet: Peter Le Neve was the son of a Ringland family – and Ringland abutted the Jerningham’s estate at Costessey, granted to Sir Henry Jerningham in 1553 by Queen Mary. As with myself, who grew up on that former estate, we can guess that Le Neve’s interest in his parent’s neighbour would have been keen. Especially since that neighbour’s genealogy stretched far beyond Tudor times. And when he later found the name repeated in Yorkshire . . .

Le Neve was methodical, as one must be when handling a vast collection. He compiled ‘calendars’ of his records. By 1689 he had already completed a ‘calendar of fines’ for the county of Norfolk, down to the reign of Edward II. His prime interest was the history of Norfolk and its families, and it was this that formed the basis of Blomefield’s History.

At the time of Walter Rye’s article on Peter Le Neve in the ‘Dictionary of National Biography’ (Vol 33, 1885-1900) the collection had been divided: many of Le Neve’s notes now were in the Bodleian Library, others were in the British Museum, some were in the Heralds’ College, some with the Norfolk and Norwich Archaeological Society, and the remainder were with a private firm in Norwich. I can find no update on this.

Walter Rye lists the items in the collection as:

- Calendars of early fines of Norfolk, Richard I to Henry VIII

- A Dictionary of the Arms of the Gentry of Norwich and Norfolk, with Explanations, Coats, Armours, and Drawings

- An Ordinary of Arms, containing many hundred arms properly blazoned and finely preserved

- An Alphabet of Arms, with some hundreds of Arms of the Gentry of Norfolk

- Le Neve’s Ordinary of Arms: a folio manuscript with some thousand coats of arms

- Grants of Arms, by Peter Le Neve

- Notes from the Pipe Rolls relating to Norfolk and Suffolk, from Henry II to Edward III

- Copies of Norfolk Pipe Rolls

- Norfolk Patents

- Placita Coronæ, Quo Warranto, Jurat. et Assis. in Norfolk, temp. Edward I

- Proofs, Pedigrees, and Names of Families, by Peter Le Neve ‘a very large collection’.

- An annotated manuscript copy of Bysshe’s ‘Visitation of Norfolk,’ 1664,

- A volume of ‘Norfolk Pedigrees,’ with arms in colours, and a transcript of a roll of arms, and ascribed to him

- An annotated manuscript copy of Harvey’s ‘Visitation of Norfolk’ of 1563

- Le Neve’s catalogue of knights between Charles II’s and Anne’s reigns (Harl. MS. 5801–2)

- A similar work in 3 vols. on baronets that was still in manuscript at the Heralds’ College.

- Some of his diary and memoranda on heraldry

- Three volumes of his letters (Harl. MSS. 4712–13 and 7525)

- And a great mass of his collections and writings among the Rawlinson MSS. (Oxford).

The young Blomefield must have thought himself in heaven. And perhaps it was amongst this material that he came upon reference to Avice Marmion, daughter of Gernegan of Tanfield, and heir to Robert Watheby of Cumberland who held the manor of Wade. And knowing that the Jernegan family of Somerleyton Hall, Suffolk, also held the manor of Wade . . . How easy to make the wrong connection.

I have looked at the sources cited by Blomefield in his account of the family. I quote the relevant passage in full, as found in ‘Hundred of Forehoe: Cossey’ (History of Norfolk, Vol 2, pp 406-419):

“The first that I meet with of this family was called

1. Hugh, without any other addition, whose son was named

2. Jernegan, and was always called Jernegan Fitz-Hugh, or the son of Hugh; he is mentioned in the Castle-Acre Register, fo. 63. b. as a witness to a deed without date, by which Brian, son of Scolland, confirmed the church of Melsombi to the monks of Castle-Acre. He married Sibill, who, in 1183, paid 100l. of her gift into the Exchequer, after her husband’s death; (fn. 18) his son was called . . .”

(fn. 18) Rot. Pip. 30 H. 2.

Pipe Roll 1184 – to be found in Le Neve’s collection.

“3. Hugh, or Hubert, son of Jernegan, (fn. 19) . . .”

(fn. 19) “He first settled the sirname of Jernegan”

“. . . who gave a large sum of money to King Henry II. and paid it into the treasury in 1182; (fn. 20) . . .”

(fn. 20) Mag. Rot. 29 H. 2. Madex History of the Exchequer, p. 190

‘The history and antiquities of the Exchequer of the kings of England, in two periods: to wit, from the Norman conquest, to the end of the reign of K. John; and from the end of the reign of K. John, to the end of the reign of K. Edward II, Vol. I’ (1769), by Thomas Madox, 1666-1727 – to give it its full title, is available online at archive.org. See quoted below the relevant passage:

“In the 29th year of K. Henry II, Hugh son of Gernegan was to pay CCCCl. of old money for his donum; He paid CCCxliijl xvs xjd in the New Money, for CCCLxxvl iijs ixd of the Old; and the remainder, to wit, xxiiijl xvjs iijd he paid in Black silver.”

Madox’s History of the Exchequer’ would have been a standard textbook for any aspiring antiquary; as, too, would be Sir William Dugdale’s (1605-1686) ‘Baronage Of England Before And After The Norman Conquest’, Camden’s ‘Britannia’, and Weaver’s ‘Discourse on Ancient Funeral Monuments’.

“. . . he [Hugh, or Hubert, son of Jernegan] was witness to a deed in 1195, by which divers lands were granted to Byland abbey in Yorkshire; (fn. 21) . . .”

(fn. 21) Regr. Abbaæ Byland, pen. P.L.N. fo 122

Blomefield probably found notes from this amongst Le Neve’s papers.

“. . . he [Hugh, or Hubert, son of Jernegan] married Maud, daughter and coheir of Thorpine, son of Rob. de Watheby of Westmorland, (fn. 22) . . . “

(fn. 22) “By whom came Wathe manor in North-Cove in Suffolk”.

Blomefield cites no source for this ‘key assertion’, which at first inclined me to assume this was Le Neve’s deduction. Yet Le Neve would have known of the Yorkshire manor..

“. . . he is mentioned by the name of Hubert de Jernegan, in the Black Book of the Exchequer, published by Mr. Herne at Oxford, 1728, vol. i. p. 301, as one of the Suffolk knights that held of the honour of Eye. . . “

Having found the name of Hugh Gernegan in Yorkshire, Blomefield now makes the second part of the connection, equating Hugh Gernegan in Yorkshire with Hubert Jernegan of Eye.

A copy of Hearne’s ‘Black Book of the Exchequer’ exists online – Liber niger Scaccarii : nec non Wilhelmi Worcestrii Annales rerum Anglicarum, cum præfatione et appendice Thomæ Hearnii ad editionem primam Oxoniæ editam – but access is by password only.

“In 1201, he [Hugh Gernegan] paid King John 20l. fine, (fn. 23) for three knights fees and an half, which laid in Yorkshire, and were held of the honour of Brittany . . .

(fn. 23) Rot. Pip. Pasch. 3 Joh. Rot. 16. indorso, in the Tally Court in the Excheuer

Another pipe roll, this dated to Easter 1202. Again, we might expect notes from this to be part of Le Neve’s collection.

“. . . [Hugh Gernegan] died in 1203, and the King granted the wardship of all his large possessions, and the marriage of his wife and children, to Robert de Veteri Ponte, or Vipount, so that he married them without disparagement to their fortunes. (fn. 24).

(fn. 24) Cart. 5 Joh. M. 11 – Charter of King John, 1204.

There is a suggestion that Robert de Vieuxpont was granted wardship of Gernegan’s widow and daughters because he was related to Gernegan’s wife, Maud, daughter of Torphin, through her maternal line (See Northern Roots). Or that he was granted it as High Sheriff of Nottinghamshire, Derbyshire and the Royal Forests. With inclusive control of the royal treasury at Nottingham castle, Robert de Vieuxpont held this extremely sensitive and powerful position from 1203 to 1208. But, in fact, King John granted this wardship as reward for his support in Normandy – he had been present at the relief of Mirebeau, and had received charge of several prisoners.

The previous year (1202) King John had granted to him Appleby and Burgh castles along with the entire bailiwick of Westmorland. This was the stamping ground of Robert de Watheby and his son Thorpine. The widow Maud and her children were now vassals of Robert de Vieuxpont. And so the king . . .

“further . . . sold to him for a hundred marks the custody of the heirs, land, and widow of Hugh Gernegan . . . (Rot. de Liberate, p. 66).”

Dictionary of National Biography,1885-1900, Volume 58: Robert de Vieuxpont by William Hunt.

Blomefield’s account of the early years of the Jernegan family is a tangle from northern and southern sources. We might guess that Peter Le Neve laid the foundation with his notes regarding Gernegan of Tanfield, and his daughter and heir Avice Marmion who had a claim on the manor of Wath – that is, Wath in Yorkshire.

It was a noteworthy claim as we saw in the first of this current series, Gernegan Case Re-Opened. The manor and its church had been granted, before 1156, to the abbey of Mont St. Michel. Yet, in total disregard, Alan III Lord of Richmond had subsequently granted it to Brian of Bedale who in turn had enfeoffed it to Gernegan III, son of Hugh (and father of Avice Marmion). In 1176-77, the monks of Mont St. Michel brought a plea concerning said land before the Pope. Yet in 1239 it was still unresolved. At this point Sir Robert Marmion offered to prove by duel that the manor was his, acquired through marriage to Avis, daughter and heir of Gernegan – and the abbot unwisely accepted.

It is almost certain that it was Blomefield, and not Le Neve who had spent considerable time in Yorkshire, who muddled the Suffolk manor of Wade with the Yorkshire Wath. Added to the fact the first notice of Gernegan was at Castle Acre priory in Norfolk, the connection was made, and stuck fast. Not even English Heritage has been able to untangle it. I specifically asked them whence the story of Robert of Watheby’s connection to Wade Manor at North Cove and they emailed back with a link to Blomefield’s ‘History’ at BHOL.

So, do we still believe that Gernagot of Tanfield, York and Whitby is also Gernagod of Sussex and Suffolk? I believe not. These were two different people – though both were of Breton families, the one a vassal of the lords of Gaël-Montort, the other, if not of the Lords Pontchateau, then at least from that same southern region.

And I’d like to add a note here that the village of Ros, which de Courson gives as in the parish of Bain-sur-l’Oust, was in fact the site of the abbey of Redon. I thank infobretagne.com for that information.

Back To Beginnings

Weaver’s story of Jernegan’s Danish roots

There is still much of the Jernegan story left untold, still acres of research begging attention. What is the story behind John de Pinkeny, son of Hubert Gernegan who in 1246 held land in Charfield in Suffolk? Who was Gernagois who, with his wife Albereda, witnessed a charter by Gilbert Crispin, in-law of William Malet, at Rouen in 1091? Who are the many other Jarnogons who stood as witness to the many Breton charters? Though many were monks, and with only a name given there is no chance of recovering their stories, yet some were priests. Since at this period the Breton priest was still a family function there is some chance of tracing their connections. Then there are the Jarnogons who were sons of . . .: of Trelohen, of Barbot Vicarius, of Rivallon, of Rioc de Port, of Orion, of ‘William’. There was a Jarnogon de Rochefort, and a Jarnogon de Malonide (possibly St Malo) who was a steward, though we’re not told steward of where. But the one that most intrigues me is Brother Gernagon the Almoner of the St John’s Hospitallers.

But my intention, a year ago when I started the first series, was to discover the source of that unlikely story:

“Anno M. xxx. Canute King of Denmarke, and of England after his return from Rome, brought diverse captains and souldiers from Denmark, whereof the greatest part were christened here in England, and began to settle themselves here, of whom, Jernegan, or Jernengham, and Jenhingho, now Jennings, were of the most esteem with Canute, who gave unto the said Jerningham, certain Royalties, and at a Parliament held at Oxford, the said King Canute did give unto the said Jerningham, certaine mannors in Norfolke, and to Jennings, certain manors lying upon the sea side, near Horwich in Suffolke, in regard of their former services done to his father Swenus, King of Denmark.”

So says Weaver in his Funeral Monuments, and Blomefield reluctantly quotes him. Yet the ‘certaine mannors in Norfolke’ in itself gives the lie. For there is no evidence of the Jernegan name in Norfolk before1263, when in the ‘Close Rolls of Henry III (volume 12: 1261-1264, pp. 299-307.) we find:

“Alexander Crisping’ venit die Jovis proxima ante festum Sancte Trinitatis et petiit terram Hugonis Gernegan in Stanhan Gernegan, Horham et Hethull eidem Hugoni etc. que capta etc.propter defaltam etc. coram justiciariis de Banco versus R. regem Alemannie.”

“Alexander Crisping, on the Thursday before the feast of the Holy Trinity, claimed the land of Hugh Gernegan in Stanhan Gernegans, Horham and Hethull . . . because of default . . .”

Though it might be of relevance that at the time of the Domesday Survey, though one manor at Hethel was held by Roger Bigod, a second was held by ‘Judicael the Priest’. Judicael, a true Breton name.

But what of this claim of Weaver’s that had even Blomefield blenching?

“Somerly [writes Weaver]:

“The habitation in antient times of FITZ-OSBERT, from whom it is come lineally to the worshipful antient family of the JERNEGANS, knights of high esteem in these parts, saith CAMDEN in this tract … the name [of Jernegan] hath been of exemplary note before the conquest ; if you will believe thus much as followeth, taken out of the pedigree of the JERNINGHAMS, by a judicious gentleman . . .” [There follows the above account of Canute.]

From ‘Weaver’s Discourse on Ancient Funeral Monuments, Page 502, The Diocese of Norwich.

By a clever juxtaposition of names, Weaver implies the story is had from Camden. Yet ll Camden says of the Jernegan family is:

“Within the land, hard by Yare is situate Somerley towne, the habitation in ancient time of Fitz-Osbert, from whom it is come lineally to the worshipfull ancient family of the Jernegans, Knights of high esteeme in these parts.”

And so I shall conclude this series with the words of one of my readers:

“. . . at the time of Weaver’s ‘Ancient Funeral Monuments’ (1631) it was very popular to disassociate yourself with any potential Norman connection to the past.”

I would add that from the time of the Hundred Years War that probably was so. Gernegan might be a Breton name but to the English, if it was across the Channel, it was France.